etext or this "small print!"

statement. You may however, if you wish, distribute this etext in

machine readable binary, compressed, mark-up, or proprietary form,

including any form resulting from conversion by word pro- cessing or

hypertext software, but only so long as *EITHER*:

[*] The etext, when displayed, is clearly readable, and does *not*

contain characters other than those intended by the author of the work,

although tilde (~), asterisk (*) and underline (_) characters may be used

to convey punctuation intended by the author, and additional characters

may be used to indicate hypertext links; OR

[*] The etext may be readily converted by the reader at no expense into

plain ASCII, EBCDIC or equivalent form by the program that displays

the etext (as is the case, for instance, with most word processors); OR

[*] You provide, or agree to also provide on request at no additional

cost, fee or expense, a copy of the etext in its original plain ASCII form

(or in EBCDIC or other equivalent proprietary form).

[2] Honor the etext refund and replacement provisions of this "Small

Print!" statement.

[3] Pay a trademark license fee to the Project of 20% of the net profits

you derive calculated using the method you already use to calculate

your applicable taxes. If you don't derive profits, no royalty is due.

Royalties are payable to "Project Gutenberg

Association/Carnegie-Mellon University" within the 60 days following

each date you prepare (or were legally required to prepare) your annual

(or equivalent periodic) tax return.

WHAT IF YOU *WANT* TO SEND MONEY EVEN IF YOU

DON'T HAVE TO?

The Project gratefully accepts contributions in money, time, scanning

machines, OCR software, public domain etexts, royalty free copyright

licenses, and every other sort of contribution you can think of. Money

should be paid to "Project Gutenberg Association / Carnegie-Mellon

University".

*END*THE SMALL PRINT! FOR PUBLIC DOMAIN

ETEXTS*Ver.04.29.93*END*

Etext scanned by Daniel Wentzell of Leesburg, Georgia.

WILDFIRE

by ZANE GREY

CHAPTER I

For some reason the desert scene before Lucy Bostil awoke varying

emotions--a sweet gratitude for the fullness of her life there at the Ford,

yet a haunting remorse that she could not be wholly content--a vague

loneliness of soul--a thrill and a fear for the strangely calling future,

glorious, unknown.

She longed for something to happen. It might be terrible, so long as it

was wonderful. This day, when Lucy had stolen away on a forbidden

horse, she was eighteen years old. The thought of her mother, who had

died long ago on their way into this wilderness, was the one drop of

sadness in her joy. Lucy loved everybody at Bostil's Ford and

everybody loved her. She loved all the horses except her father's

favorite racer, that perverse devil of a horse, the great Sage King.

Lucy was glowing and rapt with love for all she beheld from her lofty

perch: the green-and-pink blossoming hamlet beneath her, set between

the beauty of the gray sage expanse and the ghastliness of the barren

heights; the swift Colorado sullenly thundering below in the abyss; the

Indians in their bright colors, riding up the river trail; the eagle poised

like a feather on the air, and a beneath him the grazing cattle making

black dots on the sage; the deep velvet azure of the sky; the golden

lights on the bare peaks and the lilac veils in the far ravines; the silky

rustle of a canyon swallow as he shot downward in the sweep of the

wind; the fragrance of cedar, the flowers of the spear-pointed mescal;

the brooding silence, the beckoning range, the purple distance.

Whatever it was Lucy longed for, whatever was whispered by the wind

and written in the mystery of the waste of sage and stone, she wanted it

to happen there at Bostil's Ford. She had no desire for civilization, she

flouted the idea of marrying the rich rancher of Durango. Bostil's sister,

that stern but lovable woman who had brought her up and taught her,

would never persuade her to marry against her will. Lucy imagined

herself like a wild horse--free, proud, untamed, meant for the desert;

and here she would live her life. The desert and her life seemed as one,

yet in what did they resemble each other--in what of this scene could

she read the nature of her future?

Shudderingly she rejected the red, sullen, thundering river, with its

swift, changeful, endless, contending strife--for that was tragic. And

she rejected the frowning mass of red rock, upreared, riven and split

and canyoned, so grim and aloof--for that was barren. But she accepted

the vast sloping valley of sage, rolling gray and soft and beautiful,

down to the dim mountains and purple ramparts of the horizon. Lucy

did not know what she yearned for, she did not know why the

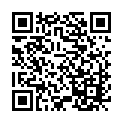

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.