I've often wished I was a lady. It must be so nice ter

wear fine clo'es an' never have ter do any work all day long.'

Willoughby thought it innocent of the girl to say this; it reminded him of his own notion

as a child--that kings and queens put on their crowns the first thing on rising in the

morning. His cordiality rose another degree.

'If being a gentleman means having nothing to do,' said he, smiling, 'I can certainly lay no

claim to the title. Life isn't all beer and skittles with me, any more than it is with you.

Which is the better reason for enjoying the present moment, don't you think? Suppose,

now, like a kind little girl, you were to show me the way to Beacon Point, which you say

is so pretty?'

She required no further persuasion. As he walked beside her through the upland fields

where the dusk was beginning to fall, and the white evening moths to emerge from their

daytime hiding-places, she asked him many personal questions, most of which he thought

fit to parry. Taking no offence thereat, she told him, instead, much concerning herself and

her family. Thus he learned her name was Esther Stables, that she and her people lived

Whitechapel way; that her father was seldom sober, and her mother always ill; and that

the aunt with whom she was staying kept the post-office and general shop in Orton

village. He learned, too, that Esther was discontented with life in general; that, though she

hated being at home, she found the country dreadfully dull; and that, consequently, she

was extremely glad to have made his acquaintance. But what he chiefly realized when

they parted was that he had spent a couple of pleasant hours talking nonsense with a girl

who was natural, simple-minded, and entirely free from that repellently protective

atmosphere with which a woman of the 'classes' so carefully surrounds herself. He and

Esther had 'made friends' with the ease and rapidity of children before they have learned

the dread meaning of 'etiquette', and they said good night, not without some talk of

meeting each other again.

Obliged to breakfast at a quarter to eight in town, Willoughby was always luxuriously

late when in the country, where he took his meals also in leisurely fashion, often reading

from a book propped up on the table before him. But the morning after his meeting with

Esther Stables found him less disposed to read than usual. Her image obtruded itself upon

the printed page, and at length grew so importunate he came to the conclusion the only

way to lay it was to confront it with the girl herself.

Wanting some tobacco, he saw a good reason for going into Orton. Esther had told him

he could get tobacco and everything else at her aunt's. He found the post-office to be one

of the first houses in the widely spaced village street. In front of the cottage was a small

garden ablaze with old-fashioned flowers; and in a large garden at one side were

apple-trees, raspberry and currant bushes, and six thatched beehives on a bench. The

bowed windows of the little shop were partly screened by sunblinds; nevertheless the

lower panes still displayed a heterogeneous collection of goods--lemons, hanks of yarn,

white linen buttons upon blue cards, sugar cones, churchwarden pipes, and tobacco jars.

A letter-box opened its narrow mouth low down in one wall, and over the door swung the

sign, 'Stamps and money-order office', in black letters on white enamelled iron.

The interior of the shop was cool and dark. A second glass-door at the back permitted

Willoughby to see into a small sitting-room, and out again through a low and

square-paned window to the sunny landscape beyond. Silhouetted against the light were

the heads of two women; the rough young head of yesterday's Esther, the lean outline and

bugled cap of Esther's aunt.

It was the latter who at the jingling of the doorbell rose from her work and came forward

to serve the customer; but the girl, with much mute meaning in her eyes, and a finger laid

upon her smiling mouth, followed behind. Her aunt heard her footfall. 'What do you want

here, Esther?' she said with thin disapproval; 'get back to your sewing.'

Esther gave the young man a signal seen only by him and slipped out into the side-garden,

where he found her when his purchases were made. She leaned over the privet-hedge to

intercept him as he passed.

'Aunt's an awful ole maid,' she remarked apologetically; 'I b'lieve she'd never let me say a

word to enny one if she could help it.'

'So you got home all right last night?' Willoughby inquired; 'what did your aunt say to

you?'

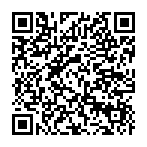

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.