the others of us, on the last day of August.

I remember that trip through the mountains in that soft, hazy, beautiful

August weather; the mountain-tops, white with snow, were wrapped

about with purple mist which twisted and shifted as if never satisfied

with their draping. The sheer rocks in the mountain-sides, washed by a

recent rain, were streaked with dull reds and blues and yellows, like the

old-fashioned rag carpet. The rivers whose banks we followed ran blue

and green, and icy cold, darting sometimes so sharply under the track

that it jerked one's neck to follow them; and then the stately evergreens

marched always with us, like endless companies of soldiers or pilgrims

wending their way to a favorite shrine.

When we awakened the second morning, and found ourselves on the

wide prairie of Alberta, with its many harvest scenes and herds of cattle,

and the gardens all in bloom, one of the boys said, waving his hand at a

particularly handsome house set in a field of ripe wheat, "No wonder

the Germans want it!"

* * *

My story really begins April 24, 1915. Up to that time it had been the

usual one--the training in England, with all the excitement of week-end

leave; the great kindness of English families whose friends in Canada

had written to them about us, and who had forthwith sent us their

invitations to visit them, which we did with the greatest pleasure,

enjoying every minute spent in their beautiful houses; and then the

greatest thrill of all--when we were ordered to France.

The 24th of April was a beautiful spring day of quivering sunshine,

which made the soggy ground in the part of Belgium where I was fairly

steam. The grass was green as plush, and along the front of the trenches,

where it had not been trodden down, there were yellow buttercups and

other little spring flowers whose names I did not know.

We had dug the trenches the day before, and the ground was so marshy

and wet that water began to ooze in before we had dug more than three

feet. Then we had gone on the other side and thrown up more dirt, to

make a better parapet, and had carried sand-bags from an old artillery

dug-out. Four strands of barbed wire were also put up in front of our

trenches, as a sort of suggestion of barbed-wire entanglements, but we

knew we had very little protection.

Early in the morning of the 24th, a German aeroplane flew low over

our trench, so low that I could see the man quite plainly, and could

easily have shot him, but we had orders not to fire--the object of these

orders being that we must not give away our position.

The airman saw us, of course, for he looked right down at us, and

dropped down white pencils of smoke to show the gunners where we

were. That big gray beetle sailing serenely over us, boring us with his

sharp eyes, and spying out our pitiful attempts at protection, is one of

the most unpleasant feelings I have ever had. It gives me the shivers yet!

And to think we had orders not to fire!

Being a sniper, I had a rifle fixed up with a telescopic sight, which gave

me a fine view of what was going on, and in order not to lose the

benefit of it, I cleaned out a place in a hedge, which was just in front of

the part of the trench I was in, and in this way I could see what was

happening, at least in my immediate vicinity.

We knew that the Algerians who were holding a trench to our left had

given way and stampeded, as a result of a German gas attack on the

night of April 22d. Not only had the front line broken, but, the panic

spreading, all of them ran, in many cases leaving their rifles behind

them. Three companies of our battalion had been hastily sent in to the

gap caused by the flight of the Algerians. Afterwards I heard that our

artillery had been hurriedly withdrawn so that it might not fall into the

hands of the enemy; but we did not know that at the time, though we

wondered, as the day went on, why we got no artillery support.

Before us, and about fifty yards away, were deserted farm buildings,

through whose windows I had instructions to send shots at intervals, to

discourage the enemy from putting in machine guns. To our right there

were other farm buildings where the Colonel and Adjutant were

stationed, and in the early morning I was sent there with a message

from Captain Scudamore, to see why our ammunition had not come up.

I found there

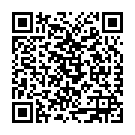

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.