spend our lives

looking on. Consider our museums for instance: they are a sign of our

breed. It makes us smile to see birds, like the magpie, with a mania for

this collecting--but only monkeyish beings could reverence museums

as we do, and pile such heterogeneous trifles and quantities in them.

Old furniture, egg-shells, watches, bits of stone. . . . And next door, a

"menagerie." Though our victory over all other animals is now aeons

old, we still bring home captives and exhibit them caged in our cities.

And when a species dies out--or is crowded (by us), off the planet--we

even collect the bones of the vanquished and show them like trophies.

Curiosity is a valuable trait. It will make the simians learn many things.

But the curiosity of a simian is as excessive as the toil of an ant. Each

simian will wish to know more than his head can hold, let alone ever

deal with; and those whose minds are active will wish to know

everything going. It would stretch a god's skull to accomplish such an

ambition, yet simians won't like to think it's beyond their powers. Even

small tradesmen and clerks, no matter how thrifty, will be eager to buy

costly encyclopedias, or books of all knowledge. Almost every simian

family, even the dullest, will think it is due to themselves to keep all

knowledge handy.

Their idea of a liberal education will therefore be a great hodge-pod

only. He who narrows his field and digs deep will be viewed as an alien.

If more than one man in a hundred should thus dare to concentrate, the

ruinous effects of being a specialist will be sadly discussed. It may

make a man exceptionally useful, they will have to admit; but still they

will feel badly, and fear that civilization will suffer.

One of their curious educational ideas--but a natural one--will be

shown in the efforts they will make to learn more than one "language."

They will set their young to spending a decade or more of their lives in

studying duplicate systems--whole systems--of chatter. Those who thus

learn several different ways to say the same things, will command

much respect, and those who learn many will be looked on with

awe--by true simians. And persons without this accomplishment will be

looked down on a little, and will actually feel quite apologetic about it

themselves.

Consider how enormously complicated a complete language must be,

with its long and arbitrary vocabulary, its intricate system of sounds;

the many forms that single words may take, especially if they are verbs;

the rules of grammar, the sentence structure, the idioms, slang and

inflections. Heavens, what a genius for tongues these simians have![1]

Where another race, after the most frightful discord and pains, might

have slowly constructed one language before this earth grew cold, this

race will create literally hundreds, each complete in itself, and many of

them with quaint little systems of writing attached. And the owners of

this linguistic gift are so humble about it, they will marvel at bees, for

their hives, and at beavers' mere dams.

[1] You remember what Kipling says in the Jungle Books, about how

disgusted the quiet animals were with the Bandarlog, because they were

eternally chattering, would never keep still. Well, this is the good side

of it.

To return, however, to their fear of being too narrow, in going to the

other extreme they will run to incredible lengths. Every civilized

simian, every day of his life, in addition to whatever older facts he has

picked up, will wish to know all the news of all the world. If he felt any

true concern to know it, this would be rather fine of him: it would

imply such a close solidarity on the part of this genus. (Such a close

solidarity would seem crushing, to others; but that is another matter.) It

won't be true concern, however, it will be merely a blind inherited

instinct. He'll forget what he's read, the very next hour, or moment. Yet

there he will faithfully sit, the ridiculous creature, reading of bombs in

Spain or floods in Thibet, and especially insisting on all the news he

can get of the kind our race loved when they scampered and fought in

the forest, news that will stir his most primitive simian feelings,--wars,

accidents, love affairs, and family quarrels.

To feed himself with this largely purposeless provender, he will pay

thousands of simians to be reporters of such events day and night; and

they will report them on such a voluminous scale as to smother or

obscure more significant news altogether. Great printed sheets will be

read by every one every day; and even the laziest of this lazy race will

not think it labor to perform

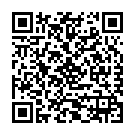

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.