Mr. Crowder and I were

smoking, after dinner, in his study. He had been speaking of people and

things that he had seen in various parts of the world, but after a time he

became a little abstracted, and allowed me to do most of the talking.

"You must excuse me," he said suddenly, when I had repeated a

question; "you must not think me willingly inattentive, but I was

considering something important--very important. Ever since you have

been here, --almost ever since I have known you, I might say,--the

desire has been growing upon me to tell you something known to no

living being but myself."

This offer did not altogether please me; I had grown very fond of

Crowder, but the confidences of friends are often very embarrassing. At

this moment the study door was gently opened, and Mrs. Crowder

came in.

"No," said she, addressing her husband with a smile; "thee need not let

thy conscience trouble thee. I have not come to say anything about

gentlemen being too long over their smoking. I only want to say that

Mrs. Norris and two other ladies have just called, and I am going down

to see them. They are a committee, and will not care for the society of

gentlemen. I am sorry to lose any of your company, Mr. Randolph,

especially as you insist that this is to be your last evening with us; but I

do not think you would care anything about our ward organizations."

"Now, isn't that a wife to have!" exclaimed my host, as we resumed our

cigars. "She thinks of everybody's happiness, and even wishes us to feel

free to take another cigar if we desire it, although in her heart she

disapproves of smoking."

We settled ourselves again to talk, and as there really could be no

objection to my listening to Crowder's confidences, I made none.

"What I have to tell you," he said presently, "concerns my life, present,

past, and future. Pretty comprehensive, isn't it? I have long been

looking for some one to whom I should be so drawn by bonds of

sympathy that I should wish to tell him my story. Now, I feel that I am

so drawn to you. The reason for this, in some degree at least, is because

you believe in me. You are not weak, and it is my opinion that on

important occasions you are very apt to judge for yourself, and not to

care very much for the opinions of other people; and yet, on a most

important occasion, you allowed me to judge for you. You are not only

able to rely on yourself, but you know when it is right to rely on others.

I believe you to be possessed of a fine and healthy sense of

appreciation."

I laughed, and begged him not to bestow too many compliments upon

me, for I was not used to them.

"I am not thinking of complimenting you," he said. "I am simply telling

you what I think of you in order that you may understand why I tell you

my story. I must first assure you, however, that I do not wish to place

any embarrassing responsibility upon you by taking you into my

confidence. All that I say to you, you may say to others when the time

comes; but first I must tell the tale to you."

He sat up straight in his chair, and put down his cigar. "I will begin," he

said, "by stating that I am the Vizier of the Two-horned Alexander."

I sat up even straighter than my companion, and gazed steadfastly at

him.

"No," said he, "I am not crazy. I expected you to think that, and am

entirely prepared for your look of amazement and incipient horror. I

will ask you, however, to set aside for a time the dictates of your own

sense, and hear what I have to say. Then you can take the whole matter

into consideration, and draw your own conclusions." He now leaned

back in his chair, and went on with his story: "It would be more correct,

perhaps, for me to say that I was the Vizier of the Two-horned

Alexander, for that great personage died long ago. Now, I don't believe

you ever heard anything about the Two-horned Alexander."

I had recovered sufficiently from my surprise to assure him that he was

right.

My host nodded. "I thought so," said he; "very few people do know

anything about that powerful potentate. He lived in the time of

Abraham. He was a man of considerable culture, even of travel, and of

an adventurous disposition. I entered into the service of his court when

I was a very young man, and gradually I rose in position until I became

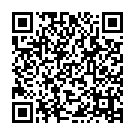

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.