I've got a girl in town."

"Same here," grinned Bert. "It's after four, now."

Chip, who at that time hadn't a girl--and didn't want one--let Silver out

for another long gallop, seeing it was Weary. Then he, too, gave up the

chase and turned back.

Glory settled to a long lope and kept steadily on, gleefully rattling the

broken bit which dangled beneath his jaws. Weary, helpless and

amused and triumphant because the race was his, sat unconcernedly in

the saddle and laid imaginary bets with himself on the outcome.

Without doubt, Glory was headed for home. Weary figured that,

barring accidents, he could catch up Blazes, in the little pasture, and

ride back to Dry Lake by the time the dance was in full swing--for the

dancing before dark would be desultory and without much spirit.

But the gate into the big field was closed and tied securely with a rope.

Glory comprehended the fact with one roll of his knowing eyes, turned

away to the left and took the trail which wound like a snake into the

foothills. Clinging warily to the level where choice was given him,

trotting where the way was rough, mile after mile he covered till even

Weary's patience showed signs of weakening.

Just then Glory turned, where a wire gate lay flat upon the ground,

crossed a pebbly creek and galloped stiffly up to the very steps of a

squat, vine-covered ranch-house where, like the Discontented

Pendulum in the fable, he suddenly stopped.

"Damn you, Glory--I could kill yuh for this!" gritted Weary, and slid

reluctantly from the saddle. For while the place seemed deserted, it was

not. There was a girl.

She lay in a hammock; sprawled would come nearer describing her

position. She had some magazines scattered around upon the porch, and

her hair hung down to the floor in a thick, dark braid. She was dressed

in a dark skirt and what, to Weary's untrained, masculine eyes, looked

like a pink gunny sack. In reality it was a kimono. She appeared to be

asleep.

Weary saw a chance of leading Glory quietly to the corral before she

woke. There he could borrow a bridle and ride back whence he came,

and he could explain about the bridle to Joe Meeker in town. Joe was

always good about lending things, anyway. He gathered the fragments

of the bit in one hand and clucked under his breath, in an agony lest his

spurs should jingle.

Glory turned upon him his beautiful, brown eyes, reproachfully

questioning.

Weary pulled steadily. Glory stretched neck and nose obediently, but as

to feet, they were down to stay.

Weary glanced anxiously toward the hammock and perspired, then

stood back and whispered language it would be a sin to repeat. Glory,

listening with unruffled calm, stood perfectly still, like a red statue in

the sunshine.

The face of the girl was hidden under one round, loose-sleeved arm.

She did not move. A faint breeze, freshening in spasmodic puffs, seized

upon the hammock, and set it swaying gently.

"Oh, damn you, Glory!" whispered Weary through his teeth. But Glory,

accustomed to being damned since he was a yearling, displayed

absolutely no interest. Indeed, he seemed inclined to doze there in the

sun.

Taking his hat--his best hat--from his head, he belabored Glory

viciously over the jaws with it; silently except for the soft thud and slap

of felt on flesh. And the mood of him was as near murder as Weary

could come. Glory had been belabored with worse things than hats

during his eventful career; he laid back his ears, shut his eyes tight and

took it meekly.

There came a gasping gurgle from the hammock, and Weary's hand

stopped in mid-air. The girl's head was burrowed in a pillow and her

slippers tapped the floor while she laughed and laughed.

Weary delivered a parting whack, put on his hat and looked at her

uncertainly; grinned sheepishly when the humor of the thing came to

him slowly, and finally sat down upon the porch steps and laughed with

her.

"Oh, gee! It was too funny," gasped the girl, sitting up and wiping her

eyes.

Weary gasped also, though it was a small matter--a common little word

of three letters. In all the messages sent him by the schoolma'am, it was

the precise, school-grammar wording of them which had irritated him

most and impressed him insensibly with the belief that she was too

prim to be quite human. The Happy Family had felt all along that they

were artists in that line, and they knew that the precise sentences ever

carried conviction of their truth. Weary mopped his perspiring face

upon a white silk handkerchief and meditated wonderingly.

"You aren't a train-robber or a horsethief, or--anything, are you?" she

asked him

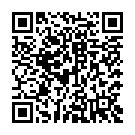

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.