a wasting, in the case of Robert H.

Norcross, was a considerable matter. The Sunday newspapers--when in

doubt--always played the income of Robert H. Norcross by periods of

months, weeks, days, hours and minutes. Every minute of his time,

their reliable statisticians computed, was worth a trifle less than

forty-seven dollars. Regardless of the waste of time, he continued to

gaze until the watch on his desk had ticked off five minutes, or two

hundred and thirty-five dollars.

The thing which had caught and held his attention was a point in the

churchyard of old Trinity near to the south door.

The Street had been remarking, for a year, that Norcross was growing

old. The change did not show in his operations. His grip on the market

was as firm as ever, his judgment as sure, his imagination as daring, his

habit of keeping his own counsel as settled. Within that year, he had

consummated the series of operations by which the L.D. and M., final

independent road needed by his system, had "come in"; within that year,

he had closed the last finger of his grip on a whole principality of our

domain. Every laborer in that area would thenceforth do a part of his

day's delving, every merchant a part of his day's bargaining, for Robert

H. Norcross. Thenceforth--until some other robber baron should wrest

it from his hands--Norcross would make laws and unmake legislatures,

dictate judgments and overrule appointments--give the high justice

while courts and assemblies trifled with the middle and the low.

Certainly the history of that year in American finance indicated no

flagging in the powers of Robert H. Norcross.

The change which the Street had marked lay in his face--it had taken on

the subtle imprint of a first frosty day. He had never looked the power

that he was. Short and slight of build, his head was rather small even

for his size, and his features were insignificant--all except the mouth,

whose wide firmness he covered by a drooping mustache, and the eyes,

which betrayed always an inner fire. The trained observer of faces

noticed this, however; every curve of his facial muscles, every plane of

the inner bone-structure, was set by nature definitely and properly in its

place to make a powerful and perfectly coördinated whole. In this facial

manifestation of mental powers, he was like one of those little athletes

who, carrying nothing superfluous, show the power, force and

endurance which is in them by no masses of overlying muscles, but

only by a masterful symmetry.

Now, in a year, the change had come over his face--the jump as abrupt

as that by which a young girl grows up--the transition from middle age

to old age. It was not so much that his full, iron-gray hair and mustache

had bleached and silvered. It was more that the cheeks were falling

from middle-aged masses to old-age creases, more that the skin was

drawing up, most that the inner energy which had vitalized his walk

and gestures was his no longer.

In the mind, too--though no one perceived that, he least of all--had

come a change. Here and there, a cell had disintegrated and collapsed.

They were not the cells which vitalized his business sense. They lay

deeper down; it was as though their very disuse for thirty years had

weakened them. In such a cell his consciousness dwelt while he gazed

on Trinity Churchyard, and especially upon that modest shaft of granite,

three graves from the south entrance. And the watch on his desk clicked

off the valuable seconds, and the electric clock on the wall jumped to

mark the passing minutes. "Click-click" from the desk--seventy-eight

cents--"Click-click"--one dollar and fifty-seven cents--"Clack" from the

wall--forty-seven dollars.

Presently, when watch and clock had chronicled four hundred and

seventy dollars of wasted time, he leaned back, looked for a moment on

the brazen September heavens above, and sighed. He might then have

turned back to his desk and the table of gross earnings, but for his

secretary.

"Mr. Bulger outside, sir," said the secretary.

"All right!" responded Mr. Norcross. In him, those two words spoke

enthusiasm; usually, a gesture or a nod was enough to bar or admit a

visitor to the royal presence. Hard behind the secretary, entered with a

bound and a breeze, Mr. Arthur Bulger. He was a tall man about

forty-five if you studied him carefully, no more than thirty-five if you

studied him casually. Not only his strong shoulders, his firm set on his

feet, his well-conditioned skin, showed the ex-athlete who has kept up

his athletics into middle age, but also that very breeze and bound of a

man whose blood runs quick and orderly through its channels. His face,

a little pudgy, took illumination from a pair of lively eyes.

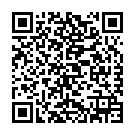

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.