(or were legally required to prepare) your annual (or equivalent periodic) tax return.

WHAT IF YOU *WANT* TO SEND MONEY EVEN IF YOU DON'T HAVE TO?

The Project gratefully accepts contributions in money, time, scanning machines, OCR software, public domain etexts, royalty free copyright licenses, and every other sort of contribution you can think of. Money should be paid to "Project Gutenberg Association".

*END*THE SMALL PRINT! FOR PUBLIC DOMAIN ETEXTS*Ver.04.29.93*END*

Scanned by Charles Keller with OmniPage Professional OCR software

THE HISTORY OF THE TELEPHONE

BY HERBERT N. CASSON

PREFACE

Thirty-five short years, and presto! the newborn art of telephony is fullgrown. Three million telephones are now scattered abroad in foreign countries, and seven millions are massed here, in the land of its birth.

So entirely has the telephone outgrown the ridicule with which, as many people can well remember, it was first received, that it is now in most places taken for granted, as though it were a part of the natural phenomena of this planet. It has so marvellously extended the facilities of conversation--that "art in which a man has all mankind for competitors"--that it is now an indispensable help to whoever would live the convenient life. The disadvantage of being deaf and dumb to all absent persons, which was universal in pre-telephonic days, has now happily been overcome; and I hope that this story of how and by whom it was done will be a welcome addition to American libraries.

It is such a story as the telephone itself might tell, if it could speak with a voice of its own. It is not technical. It is not statistical. It is not exhaustive. It is so brief, in fact, that a second volume could readily be made by describing the careers of telephone leaders whose names I find have been omitted unintentionally from this book--such indispensable men, for instance, as William R. Driver, who has signed more telephone cheques and larger ones than any other man; Geo. S. Hibbard, Henry W. Pope, and W. D. Sargent, three veterans who know telephony in all its phases; George Y. Wallace, the last survivor of the Rocky Mountain pioneers; Jasper N. Keller, of Texas and New England; W. T. Gentry, the central figure of the Southeast, and the following presidents of telephone companies: Bernard E. Sunny, of Chicago; E. B. Field, of Denver; D. Leet Wilson, of Pittsburg; L. G. Richardson, of Indianapolis; Caspar E. Yost, of Omaha; James E. Caldwell, of Nashville; Thomas Sherwin, of Boston; Henry T. Scott, of San Francisco; H. J. Pettengill, of Dallas; Alonzo Burt, of Milwaukee; John Kil- gour, of Cincinnati; and Chas. S. Gleed, of Kansas City.

I am deeply indebted to most of these men for the information which is herewith presented; and also to such pioneers, now dead, as O. E. Madden, the first General Agent; Frank L. Pope, the noted electrical expert; C. H. Haskins, of Milwaukee; George F. Ladd, of San Francisco; and Geo. F. Durant, of St. Louis.

H. N. C. PINE HILL, N. Y., June 1, 1910.

CONTENTS

CHAPTER I

THE BIRTH OF THE TELEPHONE

II THE BUILDING OF THE BUSINESS

III THE HOLDING OF THE BUSINESS

IV THE DEVELOPMENT OF THE ART

V THE EXPANSION OF THE BUSINESS

VI NOTABLE USERS OF THE TELEPHONE

VII THE TELEPHONE AND NATIONAL EFFICIENCY

VIII THE TELEPHONE IN FOREIGN COUNTRIES

IX THE FUTURE OF THE TELEPHONE

THE HISTORY OF THE TELEPHONE

CHAPTER I

THE BIRTH OF THE TELEPHONE

In that somewhat distant year 1875, when the telegraph and the Atlantic cable were the most wonderful things in the world, a tall young professor of elocution was desperately busy in a noisy machine-shop that stood in one of the narrow streets of Boston, not far from Scollay Square. It was a very hot afternoon in June, but the young professor had forgotten the heat and the grime of the workshop. He was wholly absorbed in the making of a nondescript machine, a sort of crude harmonica with a clock-spring reed, a magnet, and a wire. It was a most absurd toy in appearance. It was unlike any other thing that had ever been made in any country. The young professor had been toiling over it for three years and it had constantly baffled him, until, on this hot afternoon in June, 1875, he heard an almost inaudible sound--a faint TWANG--come from the machine itself.

For an instant he was stunned. He had been expecting just such a sound for several months, but it came so suddenly as to give him the sensation of surprise. His eyes blazed with delight, and he sprang in a passion of eagerness to an adjoining room in which stood a young mechanic who was assisting him.

"Snap that reed again, Watson," cried the apparently irrational young professor. There was one of the odd-looking machines in each room, so it appears, and the two were connected by an electric wire. Watson had snapped the reed on one

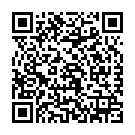

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.