was more disturbed, more restless,

more dissatisfied with himself and every thing around him, than when

first introduced to the reader's acquaintance. He eat sparingly at the

breakfast-table, and with only a slight relish. A little forced

conversation took place between him and his wife; but the thoughts of

both were remote from the subject introduced. After breakfast, Mr.

Markland strolled over his handsome grounds, and endeavoured to

awaken in his mind a new interest in what possessed so much of real

beauty. But the effort was fruitless; his thoughts were away from the

scenes in which he was actually present. Like a dreamy enthusiast on

the sea-shore, he saw, afar off, enchanted Islands faintly pictured on the

misty horizon, and could not withdraw his gaze from their ideal

loveliness.

A little way from the house was a grove, in the midst of which a

fountain threw upward its refreshing waters, that fell plashing into a

marble basin, and then went gurgling musically along over shining

pebbles. How often, with his gentle partner by his side, had Markland

lingered here, drinking in delight from every fair object by which they

were surrounded! Now he wandered amid its cool recesses, or sat by

the fountain, without having even a faint picture of the scene mirrored

in his thoughts. It was true, as he had said, "Beauty had faded from the

landscape; the air was no longer balmy with odours; the birds sang for

his ears no more; he heard not, as of old, the wind-spirits whispering to

each other in the tree-tops;" and he sighed deeply as a

half-consciousness of the change disturbed his reverie. A footfall

reached his ears, and, looking up, he saw a neighbour approaching: a

man somewhat past the prime of life, who came toward him with a

familiar smile, and, as he offered his hand, said pleasantly--

"Good morning, Friend Markland."

"Ah! good morning, Mr. Allison," was returned with a forced

cheerfulness; "I am happy to meet you."

"And happy always, I may be permitted to hope," said Mr. Allison, as

his mild yet intelligent eyes rested on the face of his neighbour.

"I doubt," answered Mr. Markland, in a voice slightly depressed from

the tone in which he had first spoken, "whether that state ever comes in

this life."

"Happiness?" inquired the other.

"Perpetual happiness; nay, even momentary happiness."

"If the former comes not to any," said Mr. Allison, "the latter, I doubt

not, is daily enjoyed by thousands."

Mr. Markland shook his head, as he replied--

"Take my case, for instance; I speak of myself, because my thought has

been turning to myself; there are few elements of happiness that I do

not possess, and yet I cannot look back to the time when I was happy."

"I hardly expected this from you, Mr. Markland," said the neighbour;

"to my observation, you always seemed one of the most cheerful of

men."

"I never was a misanthrope; I never was positively unhappy. No, I have

been too earnest a worker. But there is no disguising from myself the

fact, now I reflect upon it, that I have known but little true enjoyment

as I moved along my way through life."

"I must be permitted to believe," replied Mr. Allison, "that you are not

reading aright your past history. have been something of an observer of

men and things, and my experience leads me to this conclusion."

"He who has felt the pain, Mr. Allison, bears ever after the memory of

its existence."

"And the marks, too, if the pain has been as prolonged and severe as

your words indicate."

"But such marks, in your case, are not visible. That you have not

always found the pleasure anticipated--that you have looked restlessly

away from the present, longing for some other good than that laid by

the hand of a benignant Providence at your feet, I can well believe; for

this is my own history, as well as yours: it is the history of all

mankind."

"Now you strike the true chord, Mr. Allison. Now you state the

problem I have not skill to solve. Why is this?"

"Ah! if the world had skill to solve that problem," said the neighbour,

"it would be a wiser and happier world; but only to a few is this given."

"What is the solution? Can you declare it?"

"I fear you would not believe the answer a true one. There is nothing in

it flattering to human nature; nothing that seems to give the weary,

selfish heart a pillow to rest upon. In most cases it has a mocking

sound."

"You have taught me more than one life-lesson, Mr. Allison. Speak

freely now. I will listen patiently, earnestly, looking for instruction.

Why are we so restless and dissatisfied in the present, even

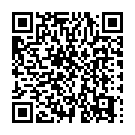

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.