To the great names of de

Tocqueville and of Taine I can but render a passing homage. The

former may be said to have opened the modern mind to the proper

method of studying the eighteenth century in France, the latter is,

perhaps, the most brilliant of writers on the subject; and no one has

recently written, or will soon write, about the time when the Revolution

was approaching without using the books of both of them. And I must

not forget the works of the Vicomte de Broc, of M. Boiteau, and of M.

Rambaud, to which I have sometimes turned for suggestion or

confirmation.

Passing to another branch of the subject, I gladly acknowledge my debt

to the Right Honorable John Morley. Differing from him in opinion

almost wherever it is possible to have an opinion, I have yet found him

thoroughly fair and accurate in matters of fact. His books on Voltaire,

Rousseau, and the Encyclopaedists, taken together, form the most

satisfactory history of French philosophy in the eighteenth century with

which I am acquainted.

Of the writers of monographs, and of the biographers, I will not speak

here in detail, although some of their books have been of very great

service to me. Such are those of M. Bailly, M. de Lavergne, M. Horn,

M. Stourm, and M. Charles Gomel, on the financial history of France;

M. de Poncins and M. Desjardins, on the cahiers; M. Rocquain on the

revolutionary spirit before the revolution, the Comte de Luçay and M.

de Lavergne, on the ministerial power and on the provincial assemblies

and estates; M. Desnoiresterres, on Voltaire; M. Scherer, on Diderot; M.

de Loménie, on Beaumarchais; and many others; and if, after all, it is

the old writers, the contemporaries, on whom I have most relied,

without the assistance of these modern writers I certainly could not

have found them all.

In treating of the Philosophers and other writers of the eighteenth

century I have not endeavored to give an abridgment of their books, but

to explain such of their doctrines as seemed to me most important and

influential. This I have done, where it was possible, in their own

language. I have quoted where I could; and in many cases where

quotation marks will not be found, the only changes from the actual

expression of the author, beyond those inevitable in translation, have

been the transference from direct to oblique speech, or some other

trifling alterations rendered necessary in my judgment by the

exigencies of grammar. On the other hand, I have tried to translate

ideas and phrases rather than words.

EDWARD J. LOWELL.

June 24, 1892.

CONTENTS.

INTRODUCTION

I. THE KING AND THE ADMINISTRATION

II. LOUIS XVI. AND HIS COURT

III. THE CLERGY

IV. THE CHURCH AND HER ADVERSARIES

V. THE CHURCH AND VOLTAIRE

VI. THE NOBILITY

VII. THE ARMY

VIII. THE COURTS OF LAW

IX. EQUALITY AND LIBERTY

X. MONTESQUIEU

XI. PARIS

XII. THE PROVINCIAL TOWNS

XIII. THE COUNTRY

XIV. TAXATION

XV. FINANCE

XVI. "THE ENCYCLOPAEDIA"

XVII. HELVETIUS, HOLBACH, AND CHASTELLUX

XVIII. ROUSSEAU'S POLITICAL WRITINGS

XIX. "LA NOUVELLE HÉLOÏSE" AND "ÉMILE"

XX. THE PAMPHLETS

XXI. THE CAHIERS

XXII. SOCIAL AND ECONOMICAL MATTERS IN THE CAHIERS

XXIII CONCLUSION

INDEX OF EDITIONS CITED

THE EVE OF THE FRENCH REVOLUTION.

INTRODUCTION.

It is characteristic of the European family of nations, as distinguished

from the other great divisions of mankind, that among them different

ideals of government and of life arise from time to time, and that before

the whole of a community has entirely adopted one set of principles,

the more advanced thinkers are already passing on to another.

Throughout the western part of continental Europe, from the sixteenth

to the eighteenth century, absolute monarchy was superseding

feudalism; and in France the victory of the newer over the older system

was especially thorough. Then, suddenly, although not quite without

warning, a third system was brought face to face with the two others.

Democracy was born full-grown and defiant. It appealed at once to two

sides of men's minds, to pure reason and to humanity. Why should a

few men be allowed to rule a great multitude as deserving as

themselves? Why should the mass of mankind lead lives full of labor

and sorrow? These questions are difficult to answer. The Philosophers

of the eighteenth century pronounced them unanswerable. They did not

in all cases advise the establishment of democratic government as a

cure for the wrongs which they saw in the world. But they attacked the

things that were, proposing other things, more or less practicable, in

their places. It seemed to these men no very difficult task to

reconstitute society and civilization, if only the faulty arrangements of

the past could be done away. They believed that men and things might

be governed by a few

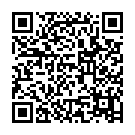

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.