length arrived; and with my enthusiasm

considerably cooled by a night of sleepless excitement and the

unpleasant consciousness that I was about, in an hour or two more, to

bid a long farewell to home and all who loved me, I descended to the

breakfast-room. My father was already there; but Eva did not come

down until the last moment; and when she made her appearance it was

evident that she had very recently been weeping. The dear girl kissed

me silently with quivering lips, and we sat down to breakfast. My

father made two or three efforts to start something in the shape of a

conversation, but it was no good; the dear old gentleman was himself

manifestly ill at ease; Eva could not speak a word for sobbing; and as

for me, I was as unable to utter a word as I was to swallow my food--a

great lump had gathered in my throat, which not only made it sore but

also threatened to choke me, and it was with the utmost difficulty that I

avoided bursting into a passion of tears. None of us ate anything, and at

length the wretched apology for a meal was brought to a conclusion,

my father read a chapter from the Bible, and we knelt down to prayers.

I will not attempt to repeat here the words of his supplication. Suffice it

to say that they went straight to my heart and lodged there, their

remembrance encompassing me about as with a seven- fold defence in

many a future hour of trial and temptation.

On rising from his knees my father invited me to accompany him to his

consulting-room, and on arriving there he handed me a chair, seated

himself directly in front of me, and said:

"Now, my dear boy, before you leave the roof which has sheltered you

from your infancy, and go forth to literally fight your own way through

the world, there is just a word or two of caution and advice which I

wish to say. You are about to embark in a profession of your own

deliberate choice, and whilst that profession is of so honourable a

character that all who wear its uniform are unquestioningly accepted as

gentlemen, it is also one which, from its very nature, exposes its

followers to many and great temptations. I will not enlarge upon these;

you are now old enough to understand the nature of many of them, and

those which you may not at present know anything about will be

readily recognisable as such when they present themselves; and a few

simple rules will, I trust, enable you to overcome them. The first rule

which I wish you to take for your guidance through life, my son, is this.

Never be ashamed to honour your Maker. Let neither false pride, nor

the gibes of your companions, nor indeed any influence whatever,

constrain you to deny Him or your dependence upon Him; never take

His name in vain, nor countenance by your continued presence any

such thing in others. Bear in mind the fact that He who holds the ocean

in the hollow of His hand is also the Guide, the Helper, and the

defender of `those who go down into the sea in ships;' and make it an

unfailing practice to seek His help and protection every day of your

life.

"Never allow yourself to contract the habit of swearing. Many

men--and, because of their pernicious example, many boys

too--habitually garnish their conversation with oaths, profanity, and

obscenity of the vilest description. It may be--though I earnestly hope

and pray it will not--that a bad example in this respect will be set you

by even your superior officers. If such should unhappily be the case,

think of this, our parting moments, and of my parting advice to you,

and never suffer yourself to be led away by such example. In the first

place it is wrong--it is distinctly sinful to indulge in such language; and

in the next place, to take much lower ground, it is vulgar,

ungentlemanly, and altogether in the very worst possible taste. It is not

even manly to do so, though many lads appear to think it so; there is

nothing manly, or noble, or dignified in the utterance of words which

inspire in the hearers--unless they be the lowest of the low--nothing

save the most extreme disgust. If you are ambitious to be classed

among the vilest and most ruffianly of your species, use such language;

but if your ambition soars higher than this, avoid it as you would the

pestilence.

"Be always strictly truthful. There are two principal incentives to

falsehood--vanity and fear. Never seek self-glorification by a falsehood.

If fame is not to be won legitimately, do without it; and never seek

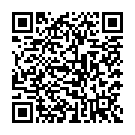

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.