seemed suddenly to swirl and

melt--I could see nothing plain! . . . What time passed--I do not

know--before their faces slowly again became visible! His face the

sober boy's--was turned away from her, and he was listening; for above

the whispering of leaves a sound of weeping came from over the hill. It

was to that he listened.

And even as I looked he slid down from out of her arms; back into the

pool, and began struggling to gain the edge. What grief and longing in

her wild face then! But she did not wail. She did not try to pull him

back; that elfish heart of dignity could reach out to what was coming, it

could not drag at what was gone. Unmoving as the boughs and water,

she watched him abandon her.

Slowly the struggling boy gained land, and lay there, breathless. And

still that sound of lonely weeping came from over the hill.

Listening, but looking at those wild, mourning eyes that never moved

from him, he lay. Once he turned back toward the water, but fire had

died within him; his hands dropped, nerveless--his young face was all

bewilderment.

And the quiet darkness of the pool waited, and the trees, and those lost

eyes of hers, and my heart. And ever from over the hill came the little

fair maiden's lonely weeping.

Then, slowly dragging his feet, stumbling, half-blinded, turning and

turning to look back, the boy groped his way out through the trees

toward that sound; and, as he went, that dark spirit-elf, abandoned,

clasping her own lithe body with her arms, never moved her gaze from

him.

I, too, crept away, and when I was safe outside in the pale evening

sunlight, peered back into the dell. There under the dark trees she was

no longer, but round and round that cage of passion, fluttering and

wailing through the leaves, over the black water, was the magpie,

flighting on its twilight wings.

I turned and ran and ran till I came over the hill and saw the boy and

the little fair, sober maiden sitting together once more on the open

slope, under the high blue heaven. She was nestling her tear- stained

face against his shoulder and speaking already of indifferent things.

And he--he was holding her with his arm and watching over her with

eyes that seemed to see something else.

And so I lay, hearing their sober talk and gazing at their sober little

figures, till I awoke and knew I had dreamed all that little allegory of

sacred and profane love, and from it had returned to reason, knowing

no more than ever which was which.

1912.

SHEEP-SHEARING

>From early morning there had been bleating of sheep in the yard, so

that one knew the creatures were being sheared, and toward evening I

went along to see. Thirty or forty naked-looking ghosts of sheep were

penned against the barn, and perhaps a dozen still inhabiting their coats.

Into the wool of one of these bulky ewes the farmer's small,

yellow-haired daughter was twisting her fist, hustling it toward Fate;

though pulled almost off her feet by the frightened, stubborn creature,

she never let go, till, with a despairing cough, the ewe had passed over

the threshold and was fast in the hands of a shearer. At the far end of

the barn, close by the doors, I stood a minute or two before shifting up

to watch the shearing. Into that dim, beautiful home of age, with its

great rafters and mellow stone archways, the June sunlight shone

through loopholes and chinks, in thin glamour, powdering with its very

strangeness the dark cathedraled air, where, high up, clung a fog of old

grey cobwebs so thick as ever were the stalactites of a huge cave. At

this end the scent of sheep and wool and men had not yet routed that

home essence of the barn, like the savour of acorns and withering beech

leaves.

They were shearing by hand this year, nine of them, counting the

postman, who, though farm-bred, "did'n putt much to the shearin'," but

had come to round the sheep up and give general aid.

Sitting on the creatures, or with a leg firmly crooked over their heads,

each shearer, even the two boys, had an air of going at it in his own

way. In their white canvas shearing suits they worked very steadily,

almost in silence, as if drowsed by the "click-clip, click- clip" of the

shears. And the sheep, but for an occasional wriggle of legs or head, lay

quiet enough, having an inborn sense perhaps of the fitness of things,

even when, once in a way, they lost more than wool; glad too, mayhap,

to be rid of their matted vestments.

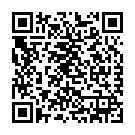

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.