shop-keepers. The reports of the battles of the Polo Club

filled her with a sweet intoxication. She knew the names of the

combatants by heart, and had her own opinion as to the comparative

eligibility of Billy Buglass and Tim Blanket, the young men most in

view at that time in the clubs of the metropolis.

Her mind was too much filled with interests of this kind to leave any

great room for her studies. She had pride enough to hold her place in

her classes, and that was all. She learned a little music, a little drawing,

a little Latin, and a little French--the French of "Stratford-atte-Bowe,"

for French of Paris was not easy of attainment at Buffland. This

language had an especial charm for her, as it seemed a connecting link

with that elysium of fashion of which her dreams were full. She once

went to the library and asked for "a nice French book." They gave her

"La Petite Fadette." She had read of George Sand in newspapers, which

had called her a "corrupter of youth." She hurried home with her book,

eager to test its corrupting qualities, and when, with locked doors and

infinite labor, she had managed to read it, she was greatly disappointed

at finding in it nothing to admire and nothing to shudder at. "How could

such a smart woman as that waste her time writing about a lot of

peasants, poor as crows, the whole lot!" was her final indignant

comment.

By the time she left the school her life had become almost as solitary as

that of the bat in the fable, alien both to bird and beast. She made no

intimate acquaintances there; her sordid and selfish dreams occupied

her too completely. Girls who admired her beauty were repelled by her

heartlessness, which they felt, but could not clearly define. Even Azalea

fell away from her, having found a stout and bald-headed railway

conductor, whose adoration made amends for his lack of romance.

Maud knew she was not liked in the school, and being, of course,

unable to attribute it to any fault of her own, she ascribed it to the fact

that her father was a mechanic and poor. This thought did not tend to

make her home happier. She passed much of her time in her own

bedroom, looking out of her window on the lake, weaving visions of

ignoble wealth and fashion out of the mists of the morning sky and the

purple and gold that made the north-west glorious at sunset. When she

sat with her parents in the evening, she rarely spoke. If she was not

gazing in the fire, with hard bright eyes and lips, in which there was

only the softness of youth, but no tender tremor of girlhood's dreams,

she was reading her papers or her novels with rapt attention. Her

mother was proud of her beauty and her supposed learning, and loved,

when she looked up from her work, to let her eyes rest upon her tall and

handsome child, whose cheeks were flushed with eager interest as she

bent her graceful head over her book. But Saul Matchin nourished a

vague anger and jealousy against her. He felt that his love was nothing

to her; that she was too pretty and too clever to be at home in his poor

house; and yet he dared not either reproach her or appeal to her

affections. His heart would fill with grief and bitterness as he gazed at

her devouring the brilliant pages of some novel of what she imagined

high life, unconscious of his glance, which would travel from her

neatly shod feet up to her hair, frizzed and banged down to her

eyebrows, "making her look," he thought, "more like a Scotch

poodle-dog than an honest girl." He hated those books which, he

fancied, stole away her heart from her home. He had once picked up

one of them where she had left it; but the high-flown style seemed as

senseless to him as the words of an incantation, and he had flung it

down more bewildered than ever. He thought there must be some

strange difference between their minds when she could delight in what

seemed so uncanny to him, and he gazed at her, reading by the

lamp-light, as over a great gulf. Even her hands holding the book made

him uneasy; for since she had grown careful of them, they were like no

hands he had ever seen on any of his kith and kin. The fingers were

long and white, and the nails were shaped like an almond, and though

the hands lacked delicacy at the articulations, they almost made

Matchin reverence his daughter as his superior, as he looked at his own.

One evening, irritated by

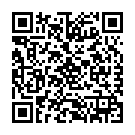

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.