provide on request at no additional

cost, fee or expense, a copy of the etext in its original plain ASCII form

(or in EBCDIC or other equivalent proprietary form).

[2] Honor the etext refund and replacement provisions of this "Small

Print!" statement.

[3] Pay a trademark license fee to the Project of 20% of the net profits

you derive calculated using the method you already use to calculate

your applicable taxes. If you don't derive profits, no royalty is due.

Royalties are payable to "Project Gutenberg

Association/Carnegie-Mellon University" within the 60 days following

each date you prepare (or were legally required to prepare) your annual

(or equivalent periodic) tax return.

WHAT IF YOU *WANT* TO SEND MONEY EVEN IF YOU

DON'T HAVE TO?

The Project gratefully accepts contributions in money, time, scanning

machines, OCR software, public domain etexts, royalty free copyright

licenses, and every other sort of contribution you can think of. Money

should be paid to "Project Gutenberg Association / Carnegie-Mellon

University".

*END*THE SMALL PRINT! FOR PUBLIC DOMAIN

ETEXTS*Ver.04.29.93*END*

THE ANCIEN REGIME

by Charles Kingsley

PREFACE

The rules of the Royal Institution forbid (and wisely) religious or

political controversy. It was therefore impossible for me in these

Lectures, to say much which had to be said, in drawing a just and

complete picture of the Ancien Regime in France. The passages

inserted between brackets, which bear on religious matters, were

accordingly not spoken at the Royal Institution.

But more. It was impossible for me in these Lectures, to bring forward

as fully as I could have wished, the contrast between the continental

nations and England, whether now, or during the eighteenth century.

But that contrast cannot be too carefully studied at the present moment.

In proportion as it is seen and understood, will the fear of revolution (if

such exists) die out among the wealthier classes; and the wish for it (if

such exists) among the poorer; and a large extension of the suffrage

will be looked on as--what it actually is--a safe and harmless

concession to the wishes--and, as I hold, to the just rights--of large

portion of the British nation.

There exists in Britain now, as far as I can see, no one of those evils

which brought about the French Revolution. There is no widespread

misery, and therefore no widespread discontent, among the classes who

live by hand-labour. The legislation of the last generation has been

steadily in favour of the poor, as against the rich; and it is even more

true now than it was in 1789, that--as Arthur Young told the French

mob which stopped his carriage--the rich pay many taxes (over and

above the poor-rates, a direct tax on the capitalist in favour of the

labourer) more than are paid by the poor. "In England" (says M. de

Tocqueville of even the eighteenth century) "the poor man enjoyed the

privilege of exemption from taxation; in France, the rich." Equality

before the law is as well- nigh complete as it can be, where some are

rich and others poor; and the only privileged class, it sometimes seems

to me, is the pauper, who has neither the responsibility of

self-government, nor the toil of self-support.

A minority of malcontents, some justly, some unjustly, angry with the

present state of things, will always exist in this world. But a majority of

malcontents we shall never have, as long as the workmen are allowed

to keep untouched and unthreatened their rights of free speech, free

public meeting, free combination for all purposes which do not provoke

a breach of the peace. There may be (and probably are) to be found in

London and the large towns, some of those revolutionary propagandists

who have terrified and tormented continental statesmen since the year

1815. But they are far fewer in number than in 1848; far fewer still (I

believe) than in 1831; and their habits, notions, temper, whole mental

organisation, is so utterly alien to that of the average Englishman, that

it is only the sense of wrong which can make him take counsel with

them, or make common cause with them. Meanwhile, every man who

is admitted to a vote, is one more person withdrawn from the

temptation to disloyalty, and enlisted in maintaining the powers that

be--when they are in the wrong, as well as when they are in the right.

For every Englishman is by his nature conservative; slow to form an

opinion; cautious in putting it into effect; patient under evils which

seem irremediable; persevering in abolishing such as seem remediable;

and then only too ready to acquiesce in the earliest practical result; to

"rest and be thankful." His faults, as well as his virtues, make him

anti-revolutionary. He is generally too dull to take in a great idea; and if

he does take it

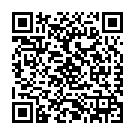

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.