single objects are

swallowed up by the great masses of light and shade, and nothing but

grand and general outlines present themselves to the eye. For three

several days we have enjoyed to the full the brightest and most glorious

of nights. Peculiarly beautiful at such a time is the Coliseum. At night it

is always closed; a hermit dwells in a little shrine within its range, and

beggars of all kinds nestle beneath its crumbling arches; the latter had

lit a fire on the arena, and a gentle wind bore down the smoke to the

ground, so that the lower portion of the ruins was quite hid by it, while

above the vast walls stood out in deeper darkness before the eye. As we

stopt at the gate to contemplate the scene through the iron gratings, the

moon shone brightly in the heavens above. Presently the smoke found

its way up the sides, and through every chink and opening, while the

moon lit it up like a cloud. The sight was exceedingly glorious. In such

a light one ought also to see the Pantheon, the Capitol, the Portico of St.

Peter's, and the other grand streets and squares--and thus sun and moon,

like the human mind, have quite a different work to do here from

elsewhere, where the vastest and yet the most elegant of masses present

themselves to their rays.

THE ANTIQUITIES OF THE CITY[4]

BY JOSEPH ADDISON

There are in Rome two sets of antiquities, the Christian, and the

heathen. The former, tho of a fresher date, are so embroiled with fable

and legend, that one receives but little satisfaction from searching into

them. The other give a great deal of pleasure to such as have met with

them before in ancient authors; for a man who is in Rome can scarce

see an object that does not call to mind a piece of a Latin poet or

historian. Among the remains of old Rome, the grandeur of the

commonwealth shows itself chiefly in works that were either necessary

or convenient, such as temples, highways, aqueducts, walls, and

bridges of the city. On the contrary, the magnificence of Rome under

the emperors is seen principally in such works as were rather for

ostentation or luxury, than any real usefulness or necessity, as in baths,

amphitheaters, circuses, obelisks, triumphal pillars, arches, and

mausoleums; for what they added to the aqueducts was rather to supply

their baths and naumachias, and to embellish the city with fountains,

than out of any real necessity there was for them....

No part of the antiquities of Rome pleased me so much as the ancient

statues, of which there is still an incredible variety. The workmanship

is often the most exquisite of anything in its kind. A man would wonder

how it were possible for so much life to enter into marble, as may be

discovered in some of the best of them; and even in the meanest, one

has the satisfaction of seeing the faces, postures, airs, and dress of those

that have lived so many ages before us. There is a strange resemblance

between the figures of the several heathen deities, and the descriptions

that the Latin poets have given us of them; but as the first may be

looked upon as the ancienter of the two, I question not but the Roman

poets were the copiers of the Greek statuaries. Tho on other occasions

we often find the statuaries took their subjects from the poets. The

Laocöon is too known an instance among many others that are to be

met with at Rome.

I could not forbear taking particular notice of the several musical

instruments that are to be seen in the hands of the Apollos, muses,

fauns, satyrs, bacchanals, and shepherds, which might certainly give a

great light to the dispute for preference between the ancient and modern

music. It would, perhaps, be no impertinent design to take off all their

models in wood, which might not only give us some notion of the

ancient music, but help us to pleasanter instruments than are now in use.

By the appearance they make in marble, there is not one

string-instrument that seems comparable to our violins, for they are all

played on either by the bare fingers, or the plectrum, so that they were

incapable of adding any length to their notes, or of varying them by

those insensible swellings, and wearings away of sound upon the same

string, which give so wonderful a sweetness to our modern music.

Besides that, the string-instruments must have had very low and feeble

voices, as may be guessed from the small proportion of wood about

them, which could not contain air enough to render the strokes, in any

considerable measure, full and sonorous. There is

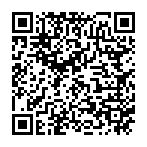

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.