you have a paper of your own, you

can give your old friend, Professor Henderson, an occasional puff."

"I shall be glad to do that," said Harry, smiling, "but I shall have to wait

some time first."

"How old are you now?"

"Sixteen."

"Then you may qualify yourself for an editor in five or six years. I

advise you to try it at any rate. The editor in America is a man of

influence."

"I do look forward to it," said Harry, seriously. "I should not be

satisfied to remain a journeyman all my life, nor even the half of it."

"I sympathize with your ambition, Harry," said the Professor, earnestly,

"and I wish you the best success. Let me hear from you occasionally."

"I should be very glad to write you, sir."

"I see the stage is at the door, and I must bid you good-by. When you

have a vacation, if you get a chance to come our way, Mrs. Henderson

and myself will be glad to receive a visit from you. Good-by!" And

with a hearty shake of the hand, Professor Henderson bade farewell to

his late assistant.

Those who have read "Bound to Rise," and are thus familiar with Harry

Walton's early history, will need no explanation of the preceding

conversation. But for the benefit of new readers, I will recapitulate

briefly the leading events in the history of the boy of sixteen who is to

be our hero.

Harry Walton was the oldest son of a poor New Hampshire farmer,

who found great difficulty is wresting from his few sterile acres a living

for his family. Nearly a year before, he had lost his only cow by a

prevalent disease, and being without money, was compelled to buy

another of Squire Green, a rich but mean neighbor, on a six months'

note, on very unfavorable terms. As it required great economy to make

both ends meet, there seemed no possible chance of his being able to

meet the note at maturity. Beside, Mr. Walton was to forfeit ten dollars

if he did not have the principal and interest ready for Squire Green. The

hard-hearted creditor was mean enough to take advantage of his poor

neighbor's necessities, and there was not the slightest chance of his

receding from his unreasonable demand. Under these circumstances

Harry, the oldest boy, asked his father's permission to go out into the

world and earn his own living. He hoped not only to do this, but to save

something toward paying his father's note. His ambition had been

kindled by reading the life of Benjamin Franklin, which had been

awarded to him as a school prize. He did not expect to emulate Franklin,

but he thought that by imitating him he might attain an honorable

position in the community.

Harry's request was not at first favorably received. To send a boy out

into the world to earn his own living is a hazardous experiment, and

fathers are less sanguine than their sons. Their experience suggests

difficulties and obstacles of which the inexperienced youth knows and

possesses nothing. But in the present case Mr. Walton reflected that the

little farming town in which he lived offered small inducements for a

boy to remain there, unless he was content to be a farmer, and this

required capital. His farm was too small for himself, and of course he

could not give Harry a part when be came of age. On the whole,

therefore, Harry's plan of becoming a mechanic seemed not so bad a

one after all. So permission was accorded, and our hero, with his little

bundle of clothes, left the paternal roof, and went out in quest of

employment.

After some adventures Harry obtained employment in a shoe-shop as

pegger. A few weeks sufficed to make him a good workman, and he

was then able to earn three dollars a week and board. Out of this sum

be hoped to save enough to pay the note held by Squire Green against

his father, but there were two unforeseen obstacles. He had the

misfortune to lose his pocket-book, which was picked up by an

unprincipled young man, by name Luke Harrison, also a shoemaker,

who was always in pecuniary difficulties, though he earned much

higher wages than Harry. Luke was unable to resist the temptation, and

appropriated the money to his own use. This Harry ascertained after a

while, but thus far had succeeded in obtaining the restitution of but a

small portion of his hard-earned savings. The second obstacle was a

sudden depression in the shoe trade which threw him out of work.

More than most occupations the shoe business is liable to these sudden

fluctuations and suspensions, and the most industrious and ambitious

workman is often compelled to spend in his enforced

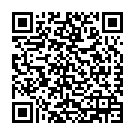

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.