own living; we can take care of ourselves

in future, so you need have no further trouble with us."

"Madam," said the doctor, making a bow with an air which displayed

his tail-feathers to advantage, "let me congratulate you on the charming

family you have raised. A finer brood of young, healthy ducks I never

saw. Give me your claw, my dear friend," he said, addressing the eldest

son. "In our barn-yard no family is more respected than that of the

ducks."

And so Madam Feathertop came off glorious at last. And when after

this the ducks used to go swimming up and down the river like so many

nabobs among the admiring hens, Dr. Peppercorn used to look after

them and say, "Ah, I had the care of their infancy!" and Mr. Gray Cock

and his wife used to say, "It was our system of education did that!"

THE NUTCRACKERS OF NUTCRACKER LODGE

Mr. and Mrs. Nutcracker were as respectable a pair of squirrels as ever

wore gray brushes over their backs. They were animals of a settled and

serious turn of mind, not disposed to run after vanities and novelties,

but filling their station in life with prudence and sobriety. Nutcracker

Lodge was a hole in a sturdy old chestnut overhanging a shady dell,

and was held to be as respectably kept an establishment as there was in

the whole forest. Even Miss Jenny Wren, the greatest gossip of the

neighbourhood, never found anything to criticise in its arrangements;

and old Parson Too-whit, a venerable owl who inhabited a branch

somewhat more exalted, as became his profession, was in the habit of

saving himself much trouble in his parochial exhortations by telling his

parishioners in short to "look at the Nutcrackers" if they wanted to see

what it was to live a virtuous life. Everything had gone on prosperously

with them, and they had reared many successive families of young

Nutcrackers, who went forth to assume their places in the forest of life,

and to reflect credit on their bringing up,--so that naturally enough they

began to have a very easy way of considering themselves models of

wisdom.

But at last it came along, in the course of events, that they had a son

named Featherhead, who was destined to bring them a great deal of

anxiety. Nobody knows what the reason is, but the fact was, that

Master Featherhead was as different from all the former children of this

worthy couple as if he had been dropped out of the moon into their nest,

instead of coming into it in the general way. Young Featherhead was a

squirrel of good parts and a lively disposition, but he was sulky and

contrary and unreasonable, and always finding matter of complaint in

everything his respectable papa and mamma did. Instead of assisting in

the cares of a family,--picking up nuts and learning other lessons proper

to a young squirrel,--he seemed to settle himself from his earliest years

into a sort of lofty contempt for the Nutcrackers, for Nutcracker Lodge,

and for all the good old ways and institutions of the domestic hole,

which he declared to be stupid and unreasonable, and entirely behind

the times. To be sure, he was always on hand at meal-times, and played

a very lively tooth on the nuts which his mother had collected, always

selecting the very best for himself; but he seasoned his nibbling with so

much grumbling and discontent, and so many severe remarks, as to

give the impression that he considered himself a peculiarly ill-used

squirrel in having to "eat their old grub," as he very unceremoniously

called it.

Papa Nutcracker, on these occasions, was often fiercely indignant, and

poor little Mamma Nutcracker would shed tears, and beg her darling to

be a little more reasonable; but the young gentleman seemed always to

consider himself as the injured party.

Now nobody could tell why or wherefore Master Featherhead looked

upon himself as injured or aggrieved, since he was living in a good hole,

with plenty to eat, and without the least care or labour of his own; but

he seemed rather to value himself upon being gloomy and dissatisfied.

While his parents and brothers and sisters were cheerfully racing up

and down the branches, busy in their domestic toils, and laying up

stores for the winter, Featherhead sat gloomily apart, declaring himself

weary of existence, and feeling himself at liberty to quarrel with

everybody and everything about him. Nobody understood him, he

said;--he was a squirrel of a peculiar nature, and needed peculiar

treatment, and nobody treated him in a way that did not grate on the

finer nerves of his feelings. He had higher notions of existence than

could be bounded by that old rotten hole in a hollow

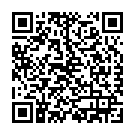

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.