elm-trees so close about the house? Her house no longer, however.

It had passed into the hands of strangers--city people, whom she did not

know. She wondered where she should live. She should want to be

independent, and she should hate to "board out."

But with the alloy of perplexity her radiant visions faded, and she fell

asleep. For the first time in all these years the milkman found locked

doors. He would not disturb the "little widdy," but when he had left the

can upon the back steps he turned away, feeling somewhat aggrieved.

The next morning, after her house was set in order and her marketing

done, Mrs. Nancy sat herself down in her porch to darn her stockings.

She had formed the habit, for Willie's sake, of doing all the work

possible out in the air and sunshine, and she still clung to all the habits

that were associated with him. Her weekly darning was a trifling piece

of work, for every hole which ventured to make its appearance in those

little gray stockings was promptly nipped in the bud.

The water was merrily flowing in the irrigating ditch, a light breeze was

rustling in the cotton woods before the door, while the passing seemed

particularly brisk. Two small boys went cantering by on one bareback

horse; a drove of cattle passed the end of the street two or three rods

away, driven by mounted cow-boys; a collection of small children in a

donkey cart halted just before her door, not of their own free will, but

in obedience to a caprice of the donkey's. They did not hurt Mrs.

Nancy's feelings by cudgelling the fat little beast, but sat laughing and

whistling and coaxing him until, of his own accord, he put his big

flapping ears forward as though they had been sails, and ambled on.

There were pretty turnouts to watch, and spirited horses, and Mrs.

Nancy found her mind constantly wandering from what she meant

should be the subject of her thoughts.

When the postman appeared around the corner he came to her gate and

lifted the latch. It was not time for her small bank dividend. The letter

must be from her husband's sister-in-law, who wrote to her about twice

a year. As Mrs. Nancy sat down to read the letter her eyes rested for a

moment upon the mountains.

"If Almira could have come with the letter she'd have thought those

snowy peaks well worth the journey," she said to herself. And then she

read the letter.

Here it is:

"DEAR NANCY,--Excuse my long silence, but I've been suffering

from rheumatism dreadfully, and haven't had the spirit to write to

anybody but my Almira. It's been so kind of lonesome since she went

away that I guess that's why the rheumatism got such a hold of me.

When you ain't got anybody belonging to you, you get kind of

low-spirited. Then the weather--it's been about as bad as I ever seen it.

Not a good hard rain, but a steady drizzle-drozzle day after day. You

can't put your foot out of doors without getting your petticoats draggled.

But you'll want to hear the news. Cousin Joshua he died last month, and

the place was sold to auction. Deacon Stebbins bought it low. He's

getting harder-fisted every year. Eliza Stebbins she's pretty far gone

with lung trouble, living in that damp old place; but he won't hear to

making any change, and she ain't got life enough left to ask for it. Both

her boys is off to Boston. Does seem as though you couldn't hold the

young folks here with ropes, and I don't know who's going to run the

farms and the corner store when we're gone. Going pretty fast we be

too. They've been eight deaths in the parish since last

Thanksgiving--Mary Jane Evans and me was counting them up last

sewing circle. Mr. Williams, the new minister, made out as we'd better

find a more cheerful subject; but we told him old Parson Edwards

before him had given us to understand that it was profitable and

edifying to the spiritual man to dwell on thoughts of death and eternity.

They do say that Parson Williams would be glad to get another parish.

He's a stirring kind of man, and there ain't overmuch to stir, round here.

I sometimes wish I could get away myself. I'd like to go down to

Boston and board for a spell, jest to see somebody passing by; but they

say board's high down there and living's poor; and, after all, it's about

as easy to stick it out here. I don't know though's I wonder that you feel

's you do about coming home. 'T ain't what you're used to out West, and

I don't suppose

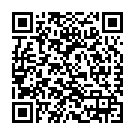

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.