and it will make you a

keener business man in the future. You have worked like a galley-slave

all summer to retrieve matters, and have taken no vacation at all. You

must take one now immediately, or you will break down altogether. Go

off to the woods; fish, hunt, follow your fancies; and the bracing

October air will make a new man of you."

"I thank you very much," Gregory began. "I suppose I do need rest. In a

few days, however, I can leave better--"

"No," interrupted Mr. Burnett, with hearty emphasis; "drop everything.

As soon as you finish that letter, be off. Don't show your face here

again till November."

"I thank you for your interest in me," said Gregory, rising. "Indeed, I

believe it would be good economy, for if I don't feel better soon I shall

be of no use here or anywhere else."

"That's it," said old Mr. Burnett, kindly. "Sick and blue, they go

together. Now be off to the woods, and send me some game. I won't

inquire too sharply whether you brought it down with lead or silver."

Gregory soon left the office, and made his arrangements to start on his

trip early the next morning. His purpose was to make a brief visit to the

home of his boyhood and then to go wherever a vagrant fancy might

lead.

The ancestral place was no longer in his family, though he was spared

the pain of seeing it in the hands of strangers. It had been purchased a

few years since by an old and very dear friend of his deceased father--a

gentleman named Walton. It had so happened that Gregory had rarely

met his father's friend, who had been engaged in business at the West,

and of his family he knew little more than that there were two

daughters--one who had married a Southern gentleman, and the other,

much younger, living with her father. Gregory had been much abroad

as the European agent of his house, and it was during such absence that

Mr. Walton had retired from business and purchased the old Gregory

homestead. The young man felt sure, however, that though a

comparative stranger himself, he would, for his father's sake, be a

welcome visitor at the home of his childhood. At any rate he

determined to test the matter, for the moment he found himself at

liberty he felt a strange and an eager longing to revisit the scenes of the

happiest portion of his life. He had meant to pay such a visit in the

previous spring, soon after his arrival from Europe, when his elation at

being made partner in the house which he so long had served as clerk

reached almost the point of happiness.

Among those who had welcomed him back was a man a little older

than himself, who, in his absence, had become known as a successful

operator in Wall Street. They had been intimate before Gregory went

abroad, and the friendship was renewed at once. Gregory prided

himself on his knowledge of the world, and was not by nature inclined

to trust hastily; and yet he did place implicit confidence in Mr. Hunting,

regarding him as a better man than himself. Hunting was an active

member of a church, and his name figured on several charities, while

Gregory had almost ceased to attend any place of worship, and spent

his money selfishly upon himself, or foolishly upon others, giving only

as prompted by impulse. Indeed, his friend had occasionally ventured

to remonstrate with him against his tendencies to dissipation, saying

that a young man of his prospects should not damage them for the sake

of passing gratification. Gregory felt the force of these words, for he

was exceedingly ambitious, and bent upon accumulating wealth and at

the same time making a brilliant figure in business circles.

In addition to the ordinary motives which would naturally lead him to

desire such success he was incited by a secret one more powerful than

all the others combined.

Before going abroad, when but a clerk, he had been the favored suitor

of a beautiful and accomplished girl. Indeed the understanding between

them almost amounted to an engagement, and he revelled in a

passionate, romantic attachment at an age when the blood is hot, the

heart enthusiastic, and when not a particle of worldly cynicism and

adverse experience had taught him to moderate his rose-hued

anticipations. She seemed the embodiment of goodness, as well as

beauty and grace, for did she not repress his tendencies to be a little fast?

Did she not, with more than sisterly solicitude, counsel him to shun

certain florid youth whose premature blossoming indicated that they

might early run to seed? and did he not, in consequence, cut Guy

Bonner, the jolliest fellow

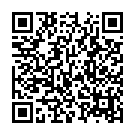

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.