discussions about thousands of different

topics. They themselves spawned communities of scientists, activists,

doctors, and patients, among so many others, dedicated to tackling

problems in collaboration across formerly prohibitive geographical and

cultural divides.

The Backlash

These new communities are perhaps why the effects of the remote,

joystick and mouse represented such a tremendous threat to business as

usual. Studies in the mid-1990s showed that families with

internet-capable computers were watching an average of nine hours less

television per week. Even more frightening to those who depended on

the mindless passivity of consumer culture, internet enthusiasts were

sharing information, ideas and whole computer programs for free!

Software known as 'freeware' and 'shareware' gave rise to a gift

economy based on community and mutual self-interest. People were

turning to alternative news and entertainment sources, which they didn't

have to pay for. Worse, they were watching fewer commercials.

Something had to be done. And it was.

It is difficult to determine exactly how intentional each of the

mainstream media's attacks were on the development of the internet

and the culture it spawned. Certainly, the many executives of media

conglomerates who contacted my colleagues and I for advice

throughout the 1990s were both threatened by the unchecked growth of

interactive culture and anxious to cash in on these new developments.

They were chagrined by the flow of viewers away from television

programming, but they hoped this shift could be managed and

ultimately exploited. While many existing content industries, such as

the music recording industry, sought to put both individual companies

and entire new categories out of business (such as Napster and other

peer-to-peer networks), the great majority of executives did not want to

see the internet entirely shut down. It was, in fact, the US government,

concerned about the spread of pornography to minors and encryption

technology to rogue nations, that took more direct actions against the

early internet's new model of open collaboration.

Although many of the leaders and top shareholders of global media

conglomerates felt quite threatened by the rise of new media, their

conscious efforts to quell the unchecked spread of interactive

technology were not the primary obstacles to the internet's natural

development. A review of articles quoting the chiefs at TimeWarner,

Newscorp, and Bertelsman reveals an industry either underestimating

or simply misunderstanding the true promise of interactive media.

The real attacks on the emerging new media culture were not

orchestrated by old men from high up in glass office towers but arose

almost as systemic responses from an old media culture responding to

the birth of its successor. It was both through the specific, if misguided,

actions of some media executives, as well as the much more unilateral

response of an entire media culture responding to a threat to the status

quo, that mainstream media began to reverse the effects of the remote,

the joystick and the mouse.

Borrowing a term from 1970s social science, media business advocates

declared that we were now living in an 'attention economy'. True

enough, the mediaspace might be infinite but there are only so many

hours in a day during which potential audience members might be

viewing a program. These units of human time became known as

eyeball-hours, and pains were taken to create TV shows and web sites

'sticky' enough to engage those eyeballs long enough to show them an

advertisement.

Perhaps coincidentally, the growth of the attention economy was

accompanied by an increase of concern over the attention spans of

young people. Channel surfing and similar behaviour became equated

with a very real but variously diagnosed childhood illness called

Attention Deficit Disorder. Children who refused to pay attention were

(much too quickly) drugged with addictive amphetamines before the

real reasons for their adaptation to the onslaught of commercial

messages were even considered.

The demystification of media, enabled by the joystick and other early

interactive technologies, was quickly reversed through the development

of increasingly opaque computer interfaces. While early DOS computer

users tended to understand a lot about how their computers stored

information and launched programs, later operating systems such as

Windows 95 put more barriers in place. Although these operating

systems make computers easier to use in some ways, they prevent users

from gaining access or command over its more intricate processes.

Now, to install a new program, users must consult the 'wizard'. What

better metaphor do we need for the remystification of the computer?

Computer literacy no longer means being able to program a computer,

but merely knowing how to use software such as Microsoft Office.

Finally, the do-it-yourself ethic of the internet community was replaced

by the new value of commerce. The communications age was

rebranded as the information age, even though the internet had never

really been about downloading files or data, but about communicating

with other people. The difference was that

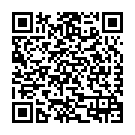

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.