we should have had at his hands blows instead of books.

Taking him, then, as he was--a man of letters--perhaps the best type of such since Dr. Johnson died in Fleet Street, what are we to say of his thirty-four volumes?

In them are to be found criticism, biography, history, politics, poetry, and religion. I mention this variety because of a foolish notion, at one time often found suitably lodged in heads otherwise empty, that Carlyle was a passionate old man, dominated by two or three extravagant ideas, to which he was for ever giving utterance in language of equal extravagance. The thirty-four volumes octavo render this opinion untenable by those who can read. Carlyle cannot be killed by an epigram, nor can the many influences that moulded him be referred to any single source. The rich banquet his genius has spread for us is of many courses. The fire and fury of the Latter-Day Pamphlets may be disregarded by the peaceful soul, and the preference given to the 'Past' of 'Past and Present,' which, with its intense and sympathetic mediaevalism, might have been written by a Tractarian. The 'Life of Sterling' is the favourite book of many who would sooner pick oakum than read 'Frederick the Great' all through; whilst the mere student of belles lettres may attach importance to the essays on Johnson, Burns, and Scott, on Voltaire and Diderot, on Goethe and Novalis, and yet remain blankly indifferent to 'Sartor Resartus' and 'The French Revolution.'

But true as this is, it is none the less true that, excepting possibly the 'Life of Schiller,' Carlyle wrote nothing not clearly recognisable as his. All his books are his very own--bone of his bone, and flesh of his flesh. They are not stolen goods, nor elegant exhibitions of recently and hastily acquired wares.

This being so, it may be as well if, before proceeding any further, I attempt, with a scrupulous regard to brevity, to state what I take to be the invariable indications of Mr. Carlyle's literary handiwork--the tokens of his presence--'Thomas Carlyle, his mark.'

First of all, it may be stated, without a shadow of a doubt, that he is one of those who would sooner be wrong with Plato than right with Aristotle; in one word, he is a mystic. What he says of Novalis may with equal truth be said of himself: 'He belongs to that class of persons who do not recognise the syllogistic method as the chief organ for investigating truth, or feel themselves bound at all times to stop short where its light fails them. Many of his opinions he would despair of proving in the most patient court of law, and would remain well content that they should be disbelieved there.' In philosophy we shall not be very far wrong if we rank Carlyle as a follower of Bishop Berkeley; for an idealist he undoubtedly was. 'Matter,' says he, 'exists only spiritually, and to represent some idea, and body it forth. Heaven and Earth are but the time-vesture of the Eternal. The Universe is but one vast symbol of God; nay, if thou wilt have it, what is man himself but a symbol of God? Is not all that he does symbolical, a revelation to sense of the mystic God-given force that is in him?--a gospel of Freedom, which he, the "Messias of Nature," preaches as he can by act and word.' 'Yes, Friends,' he elsewhere observes, 'not our logical mensurative faculty, but our imaginative one, is King over us, I might say Priest and Prophet, to lead us heavenward, or magician and wizard to lead us hellward. The understanding is indeed thy window--too clear thou canst not make it; but phantasy is thy eye, with its colour-giving retina, healthy or diseased.' It would be easy to multiply instances of this, the most obvious and interesting trait of Mr. Carlyle's writing; but I must bring my remarks upon it to a close by reminding you of his two favourite quotations, which have both significance. One from Shakespeare's _Tempest_:

'We are such stuff As dreams are made of, and our little life Is rounded with a sleep;'

the other, the exclamation of the Earth-spirit, in Goethe's _Faust_:

''Tis thus at the roaring loom of Time I ply, And weave for God the garment thou seest Him by.'

But this is but one side of Carlyle. There is another as strongly marked, which is his second note; and that is what he somewhere calls 'his stubborn realism.' The combination of the two is as charming as it is rare. No one at all acquainted with his writings can fail to remember his almost excessive love of detail; his lively taste for facts, simply as facts. Imaginary joys and sorrows may extort from him nothing but grunts and snorts; but let him only worry

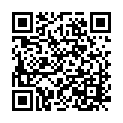

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.