Royalties are payable to "Project Gutenberg

Association/Carnegie-Mellon University" within the 60 days following

each date you prepare (or were legally required to prepare) your annual

(or equivalent periodic) tax return.

WHAT IF YOU *WANT* TO SEND MONEY EVEN IF YOU

DON'T HAVE TO?

The Project gratefully accepts contributions in money, time, scanning

machines, OCR software, public domain etexts, royalty free copyright

licenses, and every other sort of contribution you can think of. Money

should be paid to "Project Gutenberg Association / Carnegie-Mellon

University".

*END*THE SMALL PRINT! FOR PUBLIC DOMAIN

ETEXTS*Ver.04.29.93*END*

MEMOIRS OF CARWIN THE BILOQUIST [A fragment]

Charles Brockden Brown

[1803-1805]

Chapter I.

I was the second son of a farmer, whose place of residence was a

western district of Pennsylvania. My eldest brother seemed fitted by

nature for the employment to which he was destined. His wishes never

led him astray from the hay-stack and the furrow. His ideas never

ranged beyond the sphere of his vision, or suggested the possibility that

to-morrow could differ from to-day. He could read and write, because

he had no alternative between learning the lesson prescribed to him,

and punishment. He was diligent, as long as fear urged him forward,

but his exertions ceased with the cessation of this motive. The limits of

his acquirements consisted in signing his name, and spelling out a

chapter in the bible.

My character was the reverse of his. My thirst of knowledge was

augmented in proportion as it was supplied with gratification. The more

I heard or read, the more restless and unconquerable my curiosity

became. My senses were perpetually alive to novelty, my fancy teemed

with visions of the future, and my attention fastened upon every thing

mysterious or unknown.

My father intended that my knowledge should keep pace with that of

my brother, but conceived that all beyond the mere capacity to write

and read was useless or pernicious. He took as much pains to keep me

within these limits, as to make the acquisitions of my brother come up

to them, but his efforts were not equally successful in both cases. The

most vigilant and jealous scrutiny was exerted in vain: Reproaches and

blows, painful privations and ignominious penances had no power to

slacken my zeal and abate my perseverance. He might enjoin upon me

the most laborious tasks, set the envy of my brother to watch me during

the performance, make the most diligent search after my books, and

destroy them without mercy, when they were found; but he could not

outroot my darling propensity. I exerted all my powers to elude his

watchfulness. Censures and stripes were sufficiently unpleasing to

make me strive to avoid them. To effect this desirable end, I was

incessantly employed in the invention of stratagems and the execution

of expedients.

My passion was surely not deserving of blame, and I have frequently

lamented the hardships to which it subjected me; yet, perhaps, the

claims which were made upon my ingenuity and fortitude were not

without beneficial effects upon my character.

This contention lasted from the sixth to the fourteenth year of my age.

My father's opposition to my schemes was incited by a sincere though

unenlightened desire for my happiness. That all his efforts were

secretly eluded or obstinately repelled, was a source of the bitterest

regret. He has often lamented, with tears, what he called my

incorrigible depravity, and encouraged himself to perseverance by the

notion of the ruin that would inevitably overtake me if I were allowed

to persist in my present career. Perhaps the sufferings which arose to

him from the disappointment, were equal to those which he inflicted on

me.

In my fourteenth year, events happened which ascertained my future

destiny. One evening I had been sent to bring cows from a meadow,

some miles distant from my father's mansion. My time was limited, and

I was menaced with severe chastisement if, according to my custom, I

should stay beyond the period assigned.

For some time these menaces rung in my ears, and I went on my way

with speed. I arrived at the meadow, but the cattle had broken the fence

and escaped. It was my duty to carry home the earliest tidings of this

accident, but the first suggestion was to examine the cause and manner

of this escape. The field was bounded by cedar railing. Five of these

rails were laid horizontally from post to post. The upper one had been

broken in the middle, but the rest had merely been drawn out of the

holes on one side, and rested with their ends on the ground. The means

which had been used for this end, the reason why one only was broken,

and that one the uppermost, how a pair of horns could be so managed

as to effect

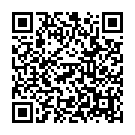

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.