ones are arising to

take their place." This attitude of mind is deplorable, if not silly, and is

a certain proof of narrow taste. It is a surety that in 1959 gloomy and

egregious persons will be saying: "Ah, yes. At the beginning of the

century there were great poets like Swinburne, Meredith, Francis

Thompson, and Yeats. Great novelists like Hardy and Conrad. Great

historians like Stubbs and Maitland, etc., etc. But they are all dead now,

and whom have we to take their place?" It is not until an age has

receded into history, and all its mediocrity has dropped away from it,

that we can see it as it is--as a group of men of genius. We forget the

immense amount of twaddle that the great epochs produced. The total

amount of fine literature created in a given period of time differs from

epoch to epoch, but it does not differ much. And we may be perfectly

sure that our own age will make a favourable impression upon that

excellent judge, posterity. Therefore, beware of disparaging the present

in your own mind. While temporarily ignoring it, dwell upon the idea

that its chaff contains about as much wheat as any similar quantity of

chaff has contained wheat.

The reason why you must avoid modern works at the beginning is

simply that you are not in a position to choose among modern works.

Nobody at all is quite in a position to choose with certainty among

modern works. To sift the wheat from the chaff is a process that takes

an exceedingly long time. Modern works have to pass before the bar of

the taste of successive generations. Whereas, with classics, which have

been through the ordeal, almost the reverse is the case. Your taste has

to pass before the bar of the classics. That is the point. If you differ

with a classic, it is you who are wrong, and not the book. If you differ

with a modern work, you may be wrong or you may be right, but no

judge is authoritative enough to decide. Your taste is unformed. It

needs guidance, and it needs authoritative guidance. Into the business

of forming literary taste faith enters. You probably will not specially

care for a particular classic at first. If you did care for it at first, your

taste, so far as that classic is concerned, would be formed, and our

hypothesis is that your taste is not formed. How are you to arrive at the

stage of caring for it? Chiefly, of course, by examining it and honestly

trying to understand it. But this process is materially helped by an act

of faith, by the frame of mind which says: "I know on the highest

authority that this thing is fine, that it is capable of giving me pleasure.

Hence I am determined to find pleasure in it." Believe me that faith

counts enormously in the development of that wide taste which is the

instrument of wide pleasures. But it must be faith founded on

unassailable authority.

CHAPTER V

HOW TO READ A CLASSIC

Let us begin experimental reading with Charles Lamb. I choose Lamb

for various reasons: He is a great writer, wide in his appeal, of a highly

sympathetic temperament; and his finest achievements are simple and

very short. Moreover, he may usefully lead to other and more complex

matters, as will appear later. Now, your natural tendency will be to

think of Charles Lamb as a book, because he has arrived at the stage of

being a classic. Charles Lamb was a man, not a book. It is extremely

important that the beginner in literary study should always form an idea

of the man behind the book. The book is nothing but the expression of

the man. The book is nothing but the man trying to talk to you, trying

to impart to you some of his feelings. An experienced student will

divine the man from the book, will understand the man by the book, as

is, of course, logically proper. But the beginner will do well to aid

himself in understanding the book by means of independent

information about the man. He will thus at once relate the book to

something human, and strengthen in his mind the essential notion of the

connection between literature and life. The earliest literature was

delivered orally direct by the artist to the recipient. In some respects

this arrangement was ideal. Changes in the constitution of society have

rendered it impossible. Nevertheless, we can still, by the exercise of the

imagination, hear mentally the accents of the artist speaking to us. We

must so exercise our imagination as to feel the man behind the book.

Some biographical information about Lamb should be acquired. There

are excellent

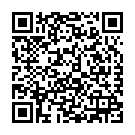

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.