touched or irritated or pleased him. When he had left Paris for Rome

she had not bidden him good-by. Jenny, her younger sister, had told

him that she was not well.

"If I had seen her then," he cried inwardly, "I might have read her

heart--and my own."

M. Renard, riding a very tall horse in the Bois, passed him and raised

his eyebrows at the sight of his pallor and his fagged yet excited look.

"There will be a new sonnet," he said to himself. "A sonnet to Despair,

or Melancholy, or Loss."

Afterward, when society became a little restive and eager, M. Renard

looked on with sardonic interest.

"That happy man, M. Villefort," he said to Madame de Castro, "is a

good soul--a good soul. He has no small jealous follies," and his smile

was scarcely a pleasant thing to see.

"There is nothing for us beyond this past," Bertha had said, and

Edmondstone had agreed with her hopelessly.

But he could not quite break away. Sometimes for a week the Villeforts

missed him, and then again they saw him every day. He spent his

mornings with them, joined them in their drives, at their opera-box, or

at the entertainments of their friends. He also fell into his old place in

the Trent household, and listened with a vague effort at interest to Mrs.

Trent's maternal gossip about the boys' college expenses, Bertha's

household, and Jenny's approaching social début He was continually

full of a feverish longing to hear of Bertha,--to hear her name spoken,

her ingoings and out-comings discussed, her looks, her belongings.

"The fact is," said Mrs. Trent, as the winter advanced, "I am anxious

about Bertha. She does not look strong. I don't know why I have not

seen it before, but all at once I found out yesterday that she is really

thin. She was always slight and even a little fragile, but now she is

actually thin. One can see the little bones in her wrists and fingers. Her

rings and her bracelets slip about quite loosely."

"And talking of being thin, mother," cried Jenny, who was a frank,

bright sixteen-year-old, "look at cousin Ralph himself. He has little

hollows in his cheeks, and his eyes are as much too big as Bertha's. Is

the sword wearing out the scabbard, Ralph? That is what they always

say about geniuses, you know."

"Ralph has not looked well for some time," said Mrs. Trent. "As for

Bertha, I think I shall scold her a little, and M. Villefort too. She has

been living too exciting a life. She is out continually. She must stay at

home more and rest. It is rest she needs."

"If you tell Arthur that Bertha looks ill "--began Jenny.

Edmondstone turned toward her sharply. "Arthur!" he repeated. "Who

is Arthur?"

Mrs. Trent answered with a comfortable laugh.

"It is M. Villefort's name," she said, "though none of us call him Arthur

but Jenny. Jenny and he are great friends."

"I like him better than any one else," said Jenny stoutly. "And I wish to

set a good example to Bertha, who never calls him anything but M.

Villefort, which is absurd. Just as if they had been introduced to each

other about a week ago."

"I always hear him address her as Madame Villefort," reflected

Edmondstone, somewhat gloomily.

"Oh yes!" answered Jenny, "that is his French way of studying her

fancies. He would consider it taking an unpardonable liberty to call her

'Bertha,' since she only favors him with 'M. Villefort.' I said to him only

the other day, 'Arthur, you are the oddest couple! You're so grand and

well-behaved, I cannot imagine you scolding Bertha a little, and I have

never seen you kiss her since you were married.' I was half frightened

after I had said it. He started as if he had been shot, and turned as pale

as death. I really felt as if I had done something frightfully improper."

"The French are so different from the Americans," said Mrs. Trent,

"particularly those of M. Villefort's class. They are beautifully

punctilious, but I don't call it quite comfortable, you know."

Her mother was not the only person who noticed a change in Bertha

Villefort. Before long it was a change so marked that all who saw her

observed it. She had become painfully frail and slight. Her face looked

too finely cut, her eyes had shadowy hollows under them, and were

always bright with a feverish excitement.

"What is the matter with your wife?" demanded Madame de Castro of

M. Villefort. Since their first meeting she had never loosened her hold

upon the husband and wife, and had particularly cultivated Bertha.

There was no change in the expression of M. Villefort, but he was

strangely pallid as he

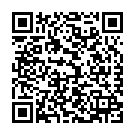

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.