and while you may not really

pause to think about it at any time, yet you are always conscious of the

rhythm and remember that it is produced by a fixed arrangement of the

accented syllables. If you would look over the poems in these volumes,

beginning even with the nursery rhymes, it would not take you long to

become familiar with all the different forms.

While study of this kind may seem tiresome at first, you will soon find

that you are making progress and will really enjoy it, and you will

never be sorry that you took the time when you were young to learn to

understand the structure of poetry.

THE GOVERNOR AND THE NOTARY

By WASHINGTON IRVING

In former times there ruled, as governor of the Alhambra[20-1], a

doughty old cavalier, who, from having lost one arm in the wars, was

commonly known by the name of El Gobernador Manco, or the

one-armed governor. He in fact prided himself upon being an old

soldier, wore his mustachios curled up to his eyes, a pair of

campaigning boots, and a toledo[20-2] as long as a spit, with his pocket

handkerchief in the basket-hilt.

He was, moreover, exceedingly proud and punctilious, and tenacious of

all his privileges and dignities. Under his sway, the immunities of the

Alhambra, as a royal residence and domain, were rigidly exacted. No

one was permitted to enter the fortress with firearms, or even with a

sword or staff, unless he were of a certain rank, and every horseman

was obliged to dismount at the gate and lead his horse by the bridle.

Now, as the hill of the Alhambra rises from the very midst of the city of

Granada, being, as it were, an excrescence of the capital, it must at all

times be somewhat irksome to the captain-general, who commands the

province, to have thus an imperium in imperio,[21-3] a petty,

independent post in the very core of his domains. It was rendered the

more galling in the present instance, from the irritable jealousy of the

old governor, that took fire on the least question of authority and

jurisdiction, and from the loose, vagrant character of the people that

had gradually nestled themselves within the fortress as in a sanctuary,

and from thence carried on a system of roguery and depredation at the

expense of the honest inhabitants of the city. Thus there was a perpetual

feud and heart-burning between the captain-general and the governor;

the more virulent on the part of the latter, inasmuch as the smallest of

two neighboring potentates is always the most captious about his

dignity. The stately palace of the captain-general stood in the Plaza

Nueva, immediately at the foot of the hill of the Alhambra, and here

was always a bustle and parade of guards, and domestics, and city

functionaries. A beetling bastion of the fortress overlooked the palace

and the public square in front of it; and on this bastion the old governor

would occasionally strut backward and forward, with his toledo girded

by his side, keeping a wary eye down upon his rival, like a hawk

reconnoitering his quarry from his nest in a dry tree.

Whenever he descended into the city it was in grand parade, on

horseback, surrounded by his guards, or in his state coach, an ancient

and unwieldy Spanish edifice of carved timber and gilt leather, drawn

by eight mules, with running footmen, outriders, and lackeys, on which

occasions he flattered himself he impressed every beholder with awe

and admiration as vicegerent of the king, though the wits of Granada

were apt to sneer at his petty parade, and, in allusion to the vagrant

character of his subjects, to greet him with the appellation of "the king

of the beggars."

One of the most fruitful sources of dispute between these two doughty

rivals was the right claimed by the governor to have all things passed

free of duty through the city, that were intended for the use of himself

or his garrison. By degrees, this privilege had given rise to extensive

smuggling. A nest of contrabandistas[22-4] took up their abode in the

hovels of the fortress and the numerous caves in its vicinity, and drove

a thriving business under the connivance of the soldiers of the garrison.

The vigilance of the captain-general was aroused. He consulted his

legal adviser and factotum, a shrewd, meddlesome Escribano or notary,

who rejoiced in an opportunity of perplexing the old potentate of the

Alhambra, and involving him in a maze of legal subtilities. He advised

the captain-general to insist upon the right of examining every convoy

passing through the gates of his city, and he penned a long letter for

him, in vindication of the right. Governor Manco was a straightforward,

cut-and-thrust old soldier, who

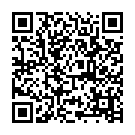

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.