son of thy servant Jesse the

Bethlehemite. And it came to pass, when he had made an end of

speaking unto Saul, that the soul of Jonathan was knit with the soul of

David, and Jonathan loved him as his own soul."

'_Elles._ Now that men are more complex, they would require so much.

For instance, if I were to have a friend, he must be an uncommunicative

man: that limits me to about thirteen or fourteen people in the world. It

is only with a man of perfect reticence that you can speak completely

without reserve. We talk together far more openly than most people;

but there is a skilful fencing even in our talk. We are not inclined to say

the whole of what we think.

'_Mil._. What I should need in a friend would be a certain breadth of

nature: I have no sympathy with people who can disturb themselves

about small things; who crave the world's good opinion; are anxious to

prove themselves always in the right; can be immersed in personal talk

or devoted to self-advancement; who seem to have grown up entirely

from the _earth_, whereas even the plants draw most of their

sustenance from the air of heaven.

'_Elles._ That is a high flight. I am not prepared to say all that. I do not

object to a little earthiness. What I should fear in friendship is the

comment, and interference, and talebearing, I often see connected with

it.

'_Mil._ That does not particularly belong to friendship, but comes

under the general head of injudicious comment on the part of those who

live with us. Divines often remind us, that in forming our ideas of the

government of Providence, we should recollect that we see only a

fragment. The same observation, in its degree, is true too as regards

human conduct. We see a little bit here and there, and assume the

nature of the whole. Even a very silly man's actions are often more to

the purpose than his friend's comments upon them.

'_Elles._ True! Then I should not like to have a man for a friend who

would bind me down to be consistent, who would form a minute theory

of me which was not to be contradicted.

'_Mil._ If he loved you as his own soul, and his soul were knit with

yours--to use the words of Scripture--he would not demand this

consistency, because each man must know and feel his own

immeasurable vacillation and inconsistency; and if he had complete

sympathy with another, he would not be greatly surprised or vexed at

that other's inconsistencies.

'_Duns._ There always seems to me a want of tenderness in what are

called friendships in the present day. Now, for instance, I don't

understand a man ridiculing his friend. The joking of intimates often

appears to me coarse and harsh. You will laugh at this in me, and think

it rather effeminate, I am afraid.

'_Mil._ No; I do not. I think a great deal of jocose raillery may pass

between intimates without the requisite tenderness being infringed

upon. If any friend had been in a painful and ludicrous position (such as

when Cardinal Balue in full dress is run away with on horseback,

which Scott comments upon as one of a class of situations combining

"pain, peril, and absurdity"), I would not remind him of it. Why should

I bring back a disagreeable impression to his mind? Besides, it would

be more painful than ludicrous to me. I should enter into his feelings

rather than into those of the ordinary spectator.

'_Duns._ I am glad we are of the same mind in this.

'_Mil._ I have also a notion that, even in the common friendships of the

world, we should be very stanch defenders of our absent friends.

Supposing that our friend's character or conduct is justly attacked in our

hearing upon some point, we should be careful to let the light and

worth of the rest of his character in upon the company, so that they

should go away with something of the impression that we have of him;

instead of suffering them to dwell only upon this fault or foible that

was commented upon, which was as nothing against him in our

hearts--mere fringe to the character, which we were accustomed to, and

rather liked than otherwise, if the truth must be told.

'_Elles._ I declare we have made out amongst us an essay on friendship,

without the fuss of writing one. I always told you our talk was better

than your writing, Milverton. Now, we only want a beginning and

ending to this peripatetic essay. What would you say to this as a

beginning?--it is to be a stately, pompous plunge into the subject, after

the Milverton fashion:--"Friendship and the Phoenix,

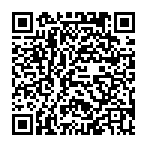

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.