me the

delight he took in studying fortification; adding, that he had sometimes

regretted having abandoned that line of life, for that he fancied he

should have been successful in it. His father would have procured him

an appointment in conformity with his wishes, had not his views

concerning him been changed by his friend, the Right Honourable Sir

George Fitzgerald Hill, then Vice-treasurer of Ireland, who gave his

son an appointment in the Vice-treasurer's office at Dublin Castle. Sir

George quickly detected the superior talents and acquirements of young

Smith, and became much attached to him; evincing peculiar satisfaction

in conversing with him, and listening to his quaint, exact, pithy answers

to questions proposed to him. About this time he was smitten with the

love of Lord Byron's poetry, which he devoured with avidity, and his

own love of verse-writing revived. He became, indeed, very anxious to

excel in poetry. He was soon tired of his official duties, and resigned

his situation in favour of his brother, who at this moment fills a

responsible office in the same department in Dublin Castle.

In the year 1826, being then in his seventeenth year, Mr. Smith entered

Trinity College, Dublin, where his whole career was, as might have

been expected, one of easy triumph. He constantly carried off the

highest classical premiums, and occasionally those in science, as well

as--whenever he tried--for composition. In 1829, he gained a

scholarship, and in the ensuing year obtained the highest honours in the

power of Trinity College to bestow, namely, the gold medal for classics.

He thought so little, however, of distinctions gained so easily, that he

either forgot, or at all events neglected, even to apply for his gold

medal till several years afterwards; when, happening to be in Dublin,

and conversation turning upon the prize which he had obtained, he said,

in a modest, casual kind of way, to a friend, "By the way, I never went

after the medal; but I think, as I'm here, I'll go and see about it." This he

did, and the medal was of course immediately delivered to its

phlegmatic oblivious winner! He was a great favourite at college, for he

bore his honours with perfect meekness and modesty, was very kind

and obliging to all desiring his assistance, and displayed, on all

occasions, that truthful simplicity and straightforwardness of character,

which, as we have already seen, he had borne from his birth. He was

much beloved, in short, by all his friends and relations; and one of the

latter, his uncle, Mr. Connor, an Irish Master in Chancery, confidently

predicted that "John William would live to be an honour to his

profession and friends." In 1829, he joined his family, who were settled

in Versailles, and spent some time there. In the ensuing year, his father,

who possessed a first-rate capacity for business, was appointed

Vice-treasurer and Paymaster-general of the forces in Ireland, and was

obliged to reside in Dublin, whither he accordingly soon afterwards

repaired with his family. His son, John William, however, remained in

London, having determined upon forthwith commencing his studies for

the English bar: a step which his father and he had for some time before

contemplated; as it appears, from the records of the Inner Temple, that

he was entered as student for the bar on the 20th June, 1827, which was

during his second year at Trinity College. The facility with which he

not only got through the requisite studies, but obtained every honour

for which he thought proper to compete, allowed of his devoting much

of his attention at that time to the acquisition of legal knowledge. He

procured a copy, therefore, of Blackstone; that, I believe, which had

appeared a year or two before, edited by the present (then Sergeant,)

Mr. Justice Coleridge,--the only edition of the Commentaries of which

he approved, and which he used to the last,--and read it through several

times with profound attention, as he has often told me; expressing

himself as having been charmed by the purity and beauty of

Blackstone's style, his remarkable power of explaining abstruse

subjects, and his perspicuous arrangement. The next book which he

read was, I believe, "Cruise's Digest of the Laws of England, respecting

Real Property," in seven volumes octavo, a standard work of great

merit; which, while at college, he read, I think, twice over, and

continued perfectly familiar with it for the rest of his life. He also read

carefully through nearly the whole of Coke upon Littleton, which he

told me he found very "troublesome," and that he had expended much

valuable time and attention on some of the most difficult portions,

which he very soon afterwards found to be utterly obsolete, particularly

mentioning those concerning "homage," "fealty," "knight-service,"

"wardship," &c. The above may seem

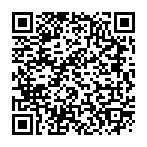

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.