The Project Gutenberg EBook of An Elegy Wrote in a Country Church

Yard (1751) and The Eton College Manuscript, by Thomas Gray

This eBook is for the use of anyone anywhere at no cost and with

almost no restrictions whatsoever. You may copy it, give it away or

re-use it under the terms of the Project Gutenberg License included

with this eBook or online at www.gutenberg.net

Title: An Elegy Wrote in a Country Church Yard (1751) and The Eton

College Manuscript

Author: Thomas Gray

Release Date: March 18, 2005 [EBook #15409]

Language: English

Character set encoding: ISO-8859-1

0. START OF THIS PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK AN ELEGY

WROTE IN A COUNTRY ***

Produced by David Starner, Diane Monico and the Online Distributed

Proofreading Team at http://www.pgdp.net

.

The Augustan Reprint Society

THOMAS GRAY

An Elegy Wrote in a Country Church Yard

(1751)

and

The Eton College Manuscript

With an Introduction by

George Sherburn

Publication Number 31

Los Angeles

Williams Andrews Clark Memorial Library

University

of California

1951

GENERAL EDITORS

H. RICHARD ARCHER, Clark Memorial Library

RICHARD C.

BOYS, University of Michigan

JOHN LOFTIS, University of

California, Los Angeles

ASSISTANT EDITOR

W. EARL BRITTON, University of Michigan

ADVISORY EDITORS

EMMETT L. AVERY, State College of Washington

BENJAMIN

BOYCE, Duke University

LOUIS I. BREDVOLD, University of

Michigan

CLEANTH BROOKS, Yale University

JAMES L.

CLIFFORD, Columbia University

ARTHUR FRIEDMAN,

University of Chicago

EDWARD NILES HOOKER, University of

California, Los Angeles LOUIS A. LANDA, Princeton University

SAMUEL H. MONK, University of Minnesota

ERNEST MOSSNER,

University of Texas

JAMES SUTHERLAND, University College,

London

H.T. SWEDENBERG, JR., University of California, Los

Angeles

INTRODUCTION

To some the eighteenth-century definition of proper poetic matter is

unacceptable; but to any who believe that true poetry may (if not

"must") consist in "what oft was thought but ne'er so well expressed,"

Gray's "Churchyard" is a majestic achievement--perhaps (accepting the

definition offered) the supreme achievement of its century. Its success,

so the great critic of its day thought, lay in its appeal to "the common

reader"; and though no friend of Gray's other work, Dr. Johnson went

on to commend the "Elegy" as abounding "with images which find a

mirrour in every mind and with sentiments to which every bosom

returns an echo." Universality, clarity, incisive lapidary

diction--these

qualities may be somewhat staled in praise of the "classical" style, yet it

is precisely in these traits that the "Elegy" proves most nobly. The

artificial figures of rhetorical arrangement that are so omnipresent in

the antitheses, chiasmuses, parallelisms, etc., of Pope and his school are

in Gray's best quatrains unobtrusive or even infrequent.

Often in the art of the period an affectation of simplicity covers and

reveals by turns a great thirst for ingenuity. Swift's prose is a fair

example; in the "Tale of a Tub" and even in "Gulliver" at first sight

there seems to appear only an honest and simple directness; but pry

beneath the surface statements, or allow yourself to be dazzled by their

coruscations of meaning, and you immediately see you are watching a

stylistic prestidigitator. The later, more orderly dignity of Dr. Johnson's

exquisitely chosen diction is likewise ingeniously studied and

self-conscious. When Gray soared into the somewhat turgid pindaric

tradition of his day, he too was slaking a thirst for rhetorical

complexities. But in the "Elegy" we have none of that. Nor do we have

artifices like the "chaste Eve" or the "meek-eyed maiden"

apostrophized in Collins and Joseph Warton. For Gray the hour when

the sky turns from opal to dusk leaves one not "breathless with

adoration," but moved calmly to placid reflection tuned to drowsy

tinklings or to a moping owl. It endures no contortions of image or of

verse. It registers the sensations of the hour and the reflections

appropriate to it--simply.

It is not difficult to be clear--so we are told by some who habitually fail

of that quality--if you have nothing subtle to say. And it has been urged

on high authority in our day that there is nothing really "fine" in Gray's

"Churchyard." However conscious Gray was in limiting his address to

"the common reader," we may be certain he was not writing to the

obtuse, the illiterate or the insensitive. He was to create an evocation of

evening: the evening of a day and the approaching night of life. The

poem was not to be perplexed by doubt; it ends on a note of "trembling

hope"--but on "hope." There are perhaps better evocations of similar

moods, but not of this precise mood. Shakespeare's poignant Sonnet

LXXIII ("That time of year"), which suggests no hope, may be one.

Blake's "Nurse's Song" is, in contrast, subtly tinged with modernistic

disillusion:

When the voices of children are heard on the green

And whisp'rings

are in the dale,

The days of my youth rise fresh in my mind,

My

face turns green and pale.

Then come home, my children, the sun is gone down,

And the dews

of

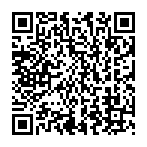

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.