the unreasonable petulance of mankind I rang the bell

and gave a curt intimation that I was ready. Then I picked up a

magazine from the table and attempted to while away the time with it,

while my companion munched silently at his toast. One of the articles

had a pencil mark at the heading, and I naturally began to run my eye

through it.

Its somewhat ambitious title was "The Book of Life," and it attempted

to show how much an observant man might learn by an accurate and

systematic examination of all that came in his way. It struck me as

being a remarkable mixture of shrewdness and of absurdity. The

reasoning was close and intense, but the deductions appeared to me to

be far-fetched and exaggerated. The writer claimed by a momentary

expression, a twitch of a muscle or a glance of an eye, to fathom a

man's inmost thoughts. Deceit, according to him, was an impossibility

in the case of one trained to observation and analysis. His conclusions

were as infallible as so many propositions of Euclid. So startling would

his results appear to the uninitiated that until they learned the processes

by which he had arrived at them they might well consider him as a

necromancer.

"From a drop of water," said the writer, "a logician could infer the

possibility of an Atlantic or a Niagara without having seen or heard of

one or the other. So all life is a great chain, the nature of which is

known whenever we are shown a single link of it. Like all other arts,

the Science of Deduction and Analysis is one which can only be

acquired by long and patient study nor is life long enough to allow any

mortal to attain the highest possible perfection in it. Before turning to

those moral and mental aspects of the matter which present the greatest

difficulties, let the enquirer begin by mastering more elementary

problems. Let him, on meeting a fellow-mortal, learn at a glance to

distinguish the history of the man, and the trade or profession to which

he belongs. Puerile as such an exercise may seem, it sharpens the

faculties of observation, and teaches one where to look and what to

look for. By a man's finger nails, by his coat-sleeve, by his boot, by his

trouser knees, by the callosities of his forefinger and thumb, by his

expression, by his shirt cuffs -- by each of these things a man's calling

is plainly revealed. That all united should fail to enlighten the

competent enquirer in any case is almost inconceivable."

"What ineffable twaddle!" I cried, slapping the magazine down on the

table, "I never read such rubbish in my life."

"What is it?" asked Sherlock Holmes.

"Why, this article," I said, pointing at it with my egg spoon as I sat

down to my breakfast. "I see that you have read it since you have

marked it. I don't deny that it is smartly written. It irritates me though.

It is evidently the theory of some arm-chair lounger who evolves all

these neat little paradoxes in the seclusion of his own study. It is not

practical. I should like to see him clapped down in a third class carriage

on the Underground, and asked to give the trades of all his

fellow-travellers. I would lay a thousand to one against him."

"You would lose your money," Sherlock Holmes remarked calmly. "As

for the article I wrote it myself."

"You!"

"Yes, I have a turn both for observation and for deduction. The theories

which I have expressed there, and which appear to you to be so

chimerical are really extremely practical -- so practical that I depend

upon them for my bread and cheese."

"And how?" I asked involuntarily.

"Well, I have a trade of my own. I suppose I am the only one in the

world. I'm a consulting detective, if you can understand what that is.

Here in London we have lots of Government detectives and lots of

private ones. When these fellows are at fault they come to me, and I

manage to put them on the right scent. They lay all the evidence before

me, and I am generally able, by the help of my knowledge of the

history of crime, to set them straight. There is a strong family

resemblance about misdeeds, and if you have all the details of a

thousand at your finger ends, it is odd if you can't unravel the thousand

and first. Lestrade is a well-known detective. He got himself into a fog

recently over a forgery case, and that was what brought him here."

"And these other people?"

"They are mostly sent on by private inquiry agencies. They are all

people who are in trouble about something,

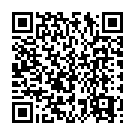

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.