mother's arms. No, she was erect on

her own small feet, tottering along in the new wooden clogs.

"My word!" exclaimed Tommie, his nose wrinkling with gratification;

"we'll have to call her Little Clogs noo."

It was in this way that Maggie's child became known in the village as

"Little Clogs." Not that it was any distinction to wear clogs in Haworth,

everyone had them; but the baby's feet were so tiny, and she was so

eager to show her new possession, that the clogs were as much noticed

as though never before seen. When she stopped in front of some

acquaintance, lifted her frock with both hands, and gazed seriously first

at her own feet and then up in her friend's face, it was only possible to

exclaim in surprise and admiration:

"Eh! To be sure. What pretty, pretty clogs baby's gotten!"

It was the middle of summer. Baby was just two years old and a month,

and the clogs were still glossy and new, when one morning Maggie

took the child with her down to Keighley as usual. It was stiflingly hot

there, after the cool breeze which blew off the moor on the hillside; the

air was thick with smoke and dust, and, as Maggie turned into the alley

where she was to leave her child, she felt how close and stuffy it was.

"'Tain't good for her here," she thought, with a sigh. "I reckon I must

mak' up my mind to leave her up yonder this hot weather."

But the baby did not seem to mind it. Maggie left her settled in the

open doorway talking cheerfully to one of her little clogs which she had

pulled off. This she filled with sand and emptied, over and over again,

chuckling with satisfaction as a stray sunbeam touched the brass clasps

and turned them into gold. In the distance she could hear the noise of

the town, and presently amongst them there came a new sound--the

beating of a drum. Baby liked music. She threw down the clog, lifted

one finger, and said "Pitty!" turning her head to look into the room. But

no one was there, for the woman of the house had gone into the back

kitchen. The noise continued, and seemed to draw baby towards it: she

got up on her feet, and staggered a little way down the alley, tottering a

good deal, for one foot had the stout little clog on it, and the other

nothing but a crumpled red sock. By degrees, however, after more than

one tumble, she got down to the end of the alley, and stood facing the

bustling street.

It was such a big, noisy world, with such a lot of people and horses and

carts in it, that she was frightened now, put out her arms, and screwed

up her face piteously, and cried, "Mammy, mammy!"

Just then a woman passed with a tambourine in her hand and a bright

coloured handkerchief over her head. She shook the tambourine and

smiled kindly at baby, showing very white teeth.

"Mammy, mammy!" said baby again, and began to sob.

"Don't cry, then, deary, and I'll take you to mammy," said the woman.

She looked quickly up the alley, no one in sight. No one in the crowded

street noticed her. She stooped, raised the child in her arms, wrapped a

shawl round her, and walked swiftly away. And that evening, when

Maggie came to fetch her little lass, she was not there; the only trace of

her was one small clog, half full of sand, on the door-step!

The woman with the tambourine hurried along, keeping the child's head

covered with her shawl, at her heels a dirty-white poodle followed

closely. The street was bustling and crowded, for it was past twelve

o'clock, and the workpeople were streaming out of the factories to go to

their dinners. If Maggie had passed the woman, she would surely have

felt that the bundle in her arms was her own little lass, even if she had

not seen one small clogged foot escaping from under the shawl. Baby

was quiet now, except for a short gasping sob now and then, for she

thought she was being taken to mammy.

On and on went the woman through the town, past the railway-station,

and at last reached a lonely country road; by that time, lulled by the

rapid, even movement and the darkness, baby had forgotten her

troubles, and was fast asleep. She slept almost without stirring for a

whole hour, and then, feeling the light on her eyes, she blinked her long

lashes, rubbed them with her fists, and stretched out her fat legs.

Next she looked up into mammy's face, as she thought, expecting the

smile which always waited for her there;

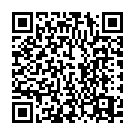

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.