Thunder arose,

and an icy wind, furious and swift as a tornado roared among the trees.

The rain, chilled almost into hail, drummed on the shingles. The birds

fell silent, the hens scurried to shelter. In ten minutes the cutting blast

died out. A dead calm succeeded. Then out burst the sun, flooding the

land with laughter! The black-birds resumed their piping, the fowls

ventured forth, and the whole valley again lay beaming and blossoming

under a perfect sky."

The following night I was in the city watching a noble performance of

"Tristan and Isolde!"

I took enormous satisfaction in the fact that I could plant peas in my

garden till noon and hear a concert in Chicago on the same day. The

arrangement seemed ideal.

On May 9th I was again at home, "the first whippoorwill sang

to-night--trees are in full leaf," I note.

In a big square room in the eastern end of the house, I set up a

handmade walnut desk which I had found in LaCrosse, and on this I

began to write in the inspiration of morning sun-shine and bird-song.

For four hours I bent above my pen, and each afternoon I sturdily

flourished spade and hoe, while mother hobbled about with cane in

hand to see that I did it right. "You need watching," she laughingly

said.

With a cook and a housemaid, a man to work the garden, and a horse to

plow out my corn and potatoes, I began to wear the composed dignity

of an earl. I pruned trees, shifted flower beds and established berry

patches with the large-handed authority of a southern planter. It was

comical, it was delightful!

To eat home-cooked meals after years of dreadful restaurants gave me

especial satisfaction, but alas! there was a flaw in my lute. We had to

eat in our living room; and when I said "Mother, one of these days I'm

going to move the kitchen to the south and build a real sure-enough

dining room in between," she turned upon me with startled gaze.

"You'd better think a long time about that," she warningly replied.

"We're perfectly comfortable the way we are."

"Comfortable? Yes, but we must begin to think of being luxurious.

There's nothing too good for you, mother."

Early in July my brother Franklin joined me in the garden work, and

then my mother's cup of contentment fairly overflowed its brim. So far

as we knew she had no care, no regret. Day by day she sat in an easy

chair under the trees, watching us as we played ball on the lawn, or cut

weeds in the garden; and each time we looked at her, we both

acknowledged a profound sense of satisfaction, of relief. Never again

would she burn in the suns of the arid plains, or cower before the winds

of a desolate winter. She was secure. "You need never work again," I

assured her. "You can get up when you please and go to bed when you

please. Your only job is to sit in the shade and boss the rest of us," and

to this she answered only with a silent, characteristic chuckle of

delight.

"The Junior," as I called my brother, enjoyed the homestead quite as

much as I. Together we painted the porch, picked berries, hoed potatoes,

and trimmed trees. Everything we did, everything we saw, recovered

for us some part of our distant boyhood. The noble lines of the hills to

the west, the weeds of the road-side, the dusty weather-beaten,

covered-bridges, the workmen in the fields, the voices of our neighbors,

the gossip of the village--all these sights and sounds awakened

deep-laid, associated tender memories. The cadence of every song, the

quality of every resounding jest made us at home, once and for all. Our

twenty-five-year stay on the level lands of Iowa and Dakota seemed

only an unsuccessful family exploration--our life in the city merely a

business, winter adventure.

To visit among the farmers--to help at haying or harvesting, brought

back minute touches of the olden, wondrous prairie world. We went

swimming in the river just as we used to do when lads, rejoicing in the

caress of the wind, the sting of the cool water, and on such expeditions

we often thought of Burton and others of our play-mates faraway, and

of Uncle David, in his California exile. "I wish he, too, could enjoy this

sweet and tranquil world," I said, and in this desire my brother joined.

We wore the rudest and simplest clothing, and hoed (when we hoed)

with furious strokes; but as the sun grew hot we usually fled to the

shade of the great maples which filled the back yard, and there, at ease,

recounted the fierce toil of the Iowa harvest fields, recalling the names

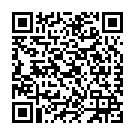

Continue reading on your phone by scaning this QR Code

Tip: The current page has been bookmarked automatically. If you wish to continue reading later, just open the

Dertz Homepage, and click on the 'continue reading' link at the bottom of the page.